Consuming ultra-processed food such as soft drinks, fast foods and frozen meals has been linked to an increased risk of depression, according to a newly published paper by Australian researchers.

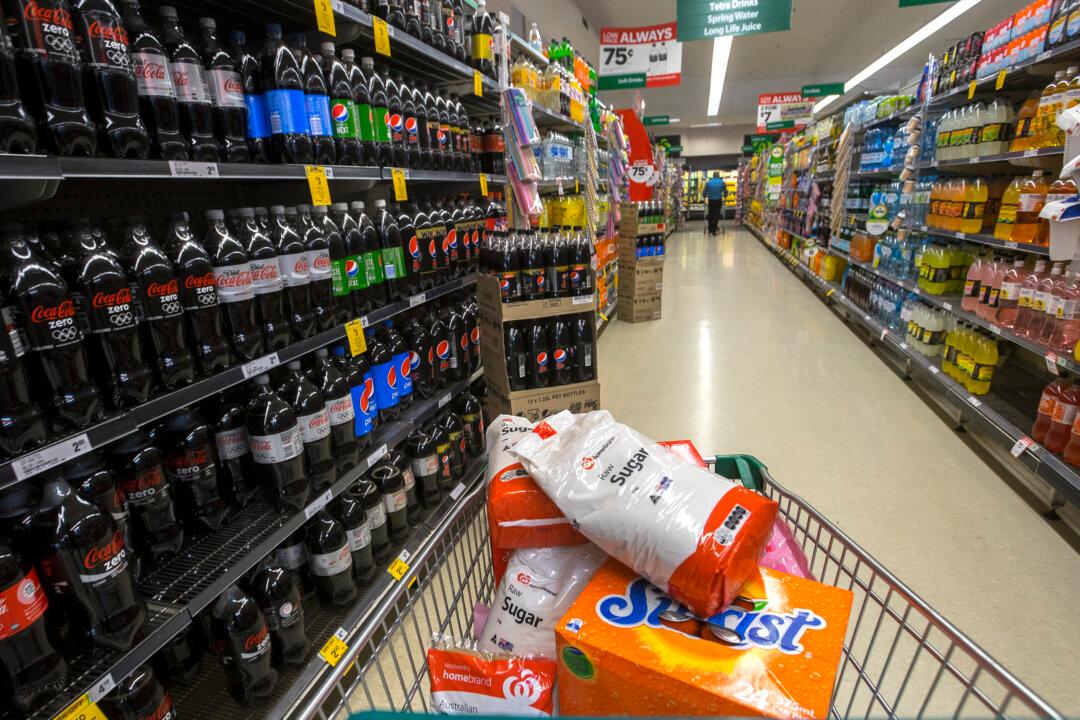

Experts from Deakin University in Victoria found that the rapid rise in cheap, convenient and heavily marketed ultra-processed foods on supermarket shelves has an adverse effect on our brains, our bodies and our planet.