The backlog of court cases and repeated hearing delays during the COVID-19 pandemic had a long-lasting impact on rape and domestic violence victims in Scotland, heightening stress and leading to witness attrition, an inquiry has heard.

The Scottish COVID-19 Inquiry’s justice impact hearing on Thursday was told that some victims face six or seven adjournments per case, making it harder for them to mentally prepare for court.

The measure affected court operations and led to record levels of repeated delays in the post-pandemic period, according to the chief executive of Victim Support Scotland (VSS), Kate Wallace.

“Victims often say they have to keep what’s happened to them at the forefront of their mind. They don’t feel they can move on with their life, feeling as though the rug’s been pulled up from under you in case of a delay, and then having to do that again and again.

“After four or five adjournments you start to doubt that the case is ever going to go ahead and stop turning up,” she told the inquiry.

Sandy Brindley, chief executive of Rape Crisis Scotland, also giving evidence to the inquiry, reported an increase in distress, anxiety, and self-harm among rape survivors during the pandemic.

Brindley added that court delays and postponed trials during the pandemic led to prolonged distress among survivors.

Wallace also reported a sharp increase in domestic violence and abuse cases owing to repeated court adjournments. She added that while efforts such as pre-recorded evidence helped reduce some trauma, survivors still faced significant challenges.

Remote Access

Established in 1985, the VSS relies on staff and volunteers to provide emotional and practical support to crime victims across Scotland. They also assist vulnerable witnesses in court.The inquiry heard that during the pandemic, over 100 volunteers left the charity between March and April 2020, mainly owing to health concerns and fears of unsafe court conditions, and most didn’t return.

The lack of digital infrastructure in Scotland’s courts during the pandemic also severely limited remote court services, said Wallace.

She told the inquiry that at a recent presentation at Eurojust in The Hague, the Dutch representatives told her that the judicial process in the Netherlands does not typically require individuals to attend court in person.

“They showed pictures of courtroom with the judge sat with a lot of screens around them, and there were no other people in the room,” she said, highlighting the contrast between the Scottish and Dutch legal systems.

Cinema Trials

Speaking about the restart of jury trials, Brindley said that the number of jurors—15 in criminal jury trials—had to be considered amid social distancing restrictions.Brindley acknowledged the leadership and creativity behind holding trials in cinemas during the crisis but noted that rape survivors had mixed reactions to the approach.

Spike in Cases

The VSS data also show that incidents of domestic abuse and violence increased immediately following the onset of the pandemic.In 2020–2021 the police in Scotland recorded 65,251 incidents of domestic abuse, an increase of 4 percent compared to the previous year. According to Wallace, the figures remained high even after the end of the pandemic.

“We are averaging as many reports weekly as we would have had monthly prior to the pandemic,” said Wallace.

She also told the inquiry that some victims experienced more crime and abuse directly as a result of the restrictions placed on them.

Support Services

The inquiry also heard that the pandemic restrictions made it harder to provide services to domestic abuse victims, such as emergency housing and face-to-face support.Wallace said that the VSS emergency assistance fund, funded by the Scottish Government, helped with removals, but travel restrictions and limited housing options worsened the situation.

Face-to-face support was disrupted, making trust-building harder. Video services like Near Me had low uptake, and phone support became more common. Digital exclusion was an issue, and providing devices to victims posed risks in abusive homes, Wallace said, adding, “If somebody’s suffering from domestic violence [and they] all of a sudden have an iPad, would that not be a red flag in the household?”

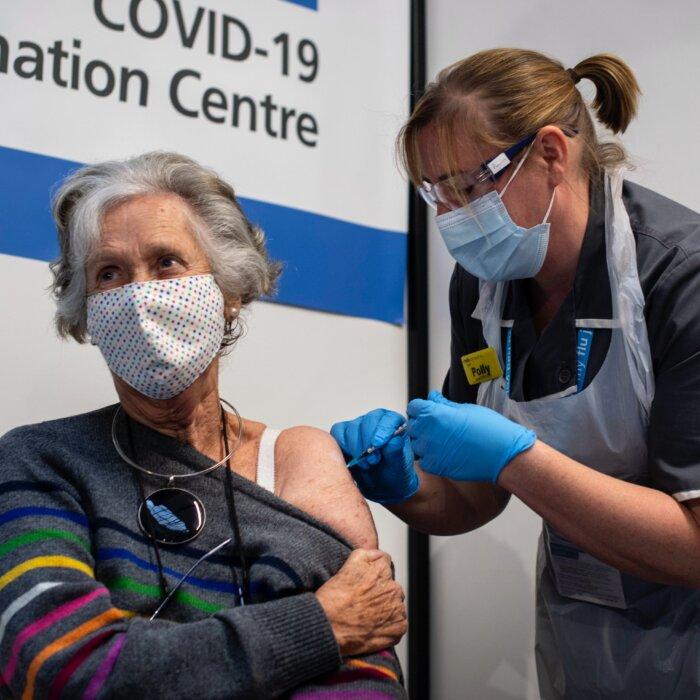

Masks also made it difficult to provide trauma-informed support to victims, particularly in sexual assault cases.

“Some people were absolutely terrified of people in face masks because potentially they may well have been attacked by someone who was wearing a face mask. It wasn’t clear whether there was any justification or whether we could make a risk assessment decision and do something different for these people.

“What we were potentially doing was retraumatising them and harming them more,” Wallace said.

The inquiry will continue holding hearings on the impact of the pandemic on justice until Feb. 28.