Geno Francis loved most things about fishing on the high seas, but his son says that in his final year, fear overshadowed that passion.

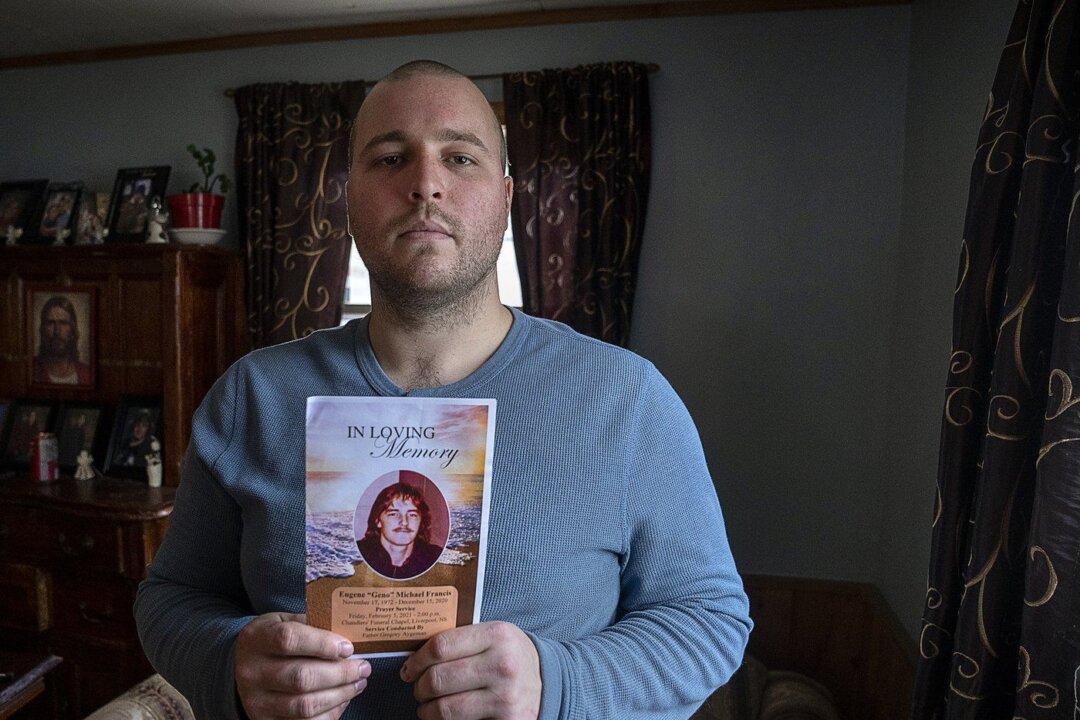

“My father said, ‘After this trip, this was it,’ because it was quite dangerous,” Michael Francis said during a recent interview at his home in Milton, N.S., a few weeks before the second anniversary of the sinking of the Chief William Saulis.