Bristol City Council (BCC) has applied for the toppled statue of Edward Colston to become a permanent museum display, the council said on Monday.

The statue of the 17th century merchant and Bristol benefactor was pulled down, vandalised, and dumped into the river during a Black Lives Matter (BLM) protest on June, 7, 2020, because of Colston’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade.

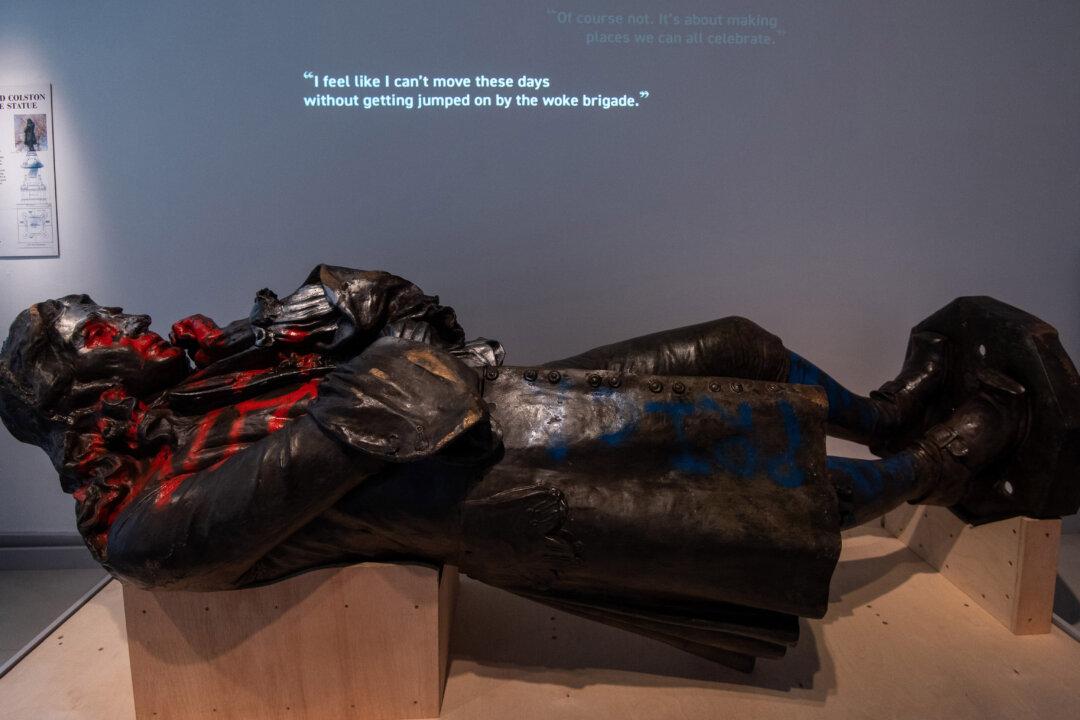

The damaged statue was recovered four days later and has been on temporary display in the M Shed museum since 2021.

BCC has filed an application to formalise the statue’s inclusion in the permanent collection of the Bristol City Council Museums service in its current state, with red and blue spray paint over it.

The council’s Development Control Committee is set to consider the application on Feb. 21.

If the plans are approved, the statue will feature as part of an upcoming exhibition at M Shed centred on the theme of “protest,” which will open in March 2024, the council said.

In the application, BCC said the statue should be “preserved in its current state and the opportunity to reflect this in the listing description is explored with Historic England.”

The council asked for the statue be “exhibited, drawing on the principles and practice of the temporary M Shed display where the statue was lying horizontally,” and for attention to be paid to “presenting the history in a nuanced, contextualised, and engaging way, including information on the broader history of the enslavement of people of African descent.”

According to the plan, the empty plinth where the statue was on will remain in Colston Avenue and a plaque will be attached to it, displaying a description of the times when the statue was unveiled and toppled and the reasons.

The plans come from the recommendations by the We Are Bristol History Commission, a committee set up by Bristol Mayor Marvin Rees with its first mission being to decide on the future of the Colston statue.

The commission’s report, published in 2020, said 80 percent of Bristolian respondents to its consultation said the statue should be kept in a museum.

Mr. Rees said: “The proposals we have developed are in direct response to the recommendations of the History Commission report which was itself informed by the views of many thousands of fellow Bristolians.

“We have shared our thoughts with Historic England on this matter too and have taken their views on board before submitting this application. I remain in support of the view that the best place for the statue is in a museum where its context, and that of what it represents to many communities can be appropriately shared with diverse audiences. We’ve already glimpsed how eager people are to learn about this context and associated history when nearly 100,000 people visited ‘The Colston Statue: What next?’ display in 2021.”

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Bristol, a key port in the west of England, became one of the main centres of the British Empire’s slave trade. But while many of those involved have been forgotten, Colston’s name lived on because he became a benefactor of the city.

The successful trader had a wide range of business interests. He became a shareholder in the Royal African Company, which had a monopoly on trade with Africa and whose members traded gold, ivory, and enslaved Africans.

He had also been an active member of the company’s governing body for 11 years.

In September 2020, Colston Hall, a popular music venue in Bristol, was renamed the Bristol Beacon, three years after the famous Bristol band Massive Attack refused to perform there until it was renamed.

Four individuals who toppled Colston’s statue and dumped it into the river were acquitted of causing criminal damage by a jury, despite having admitted to their involvement in tearing down the statue, which had been assessed to have sustained £3,750 worth of damage.

After then-Home Secretary Suella Braverman sought legal clarification on the issue, the Court of Appeal said human rights defence should not have applied in the case because the toppling of the statue was violent and caused significant damage.

The decision didn’t overturn the individuals’ acquittal as the court didn’t examine other defences used in the trial and how the jury reached its verdict.