A think tank has called the AUKUS Pillar One nuclear-propelled submarine project “overly ambitious” and says it could weaken Australia’s ability to deal with “security threats that may not involve armed conflict,” such as pandemics.

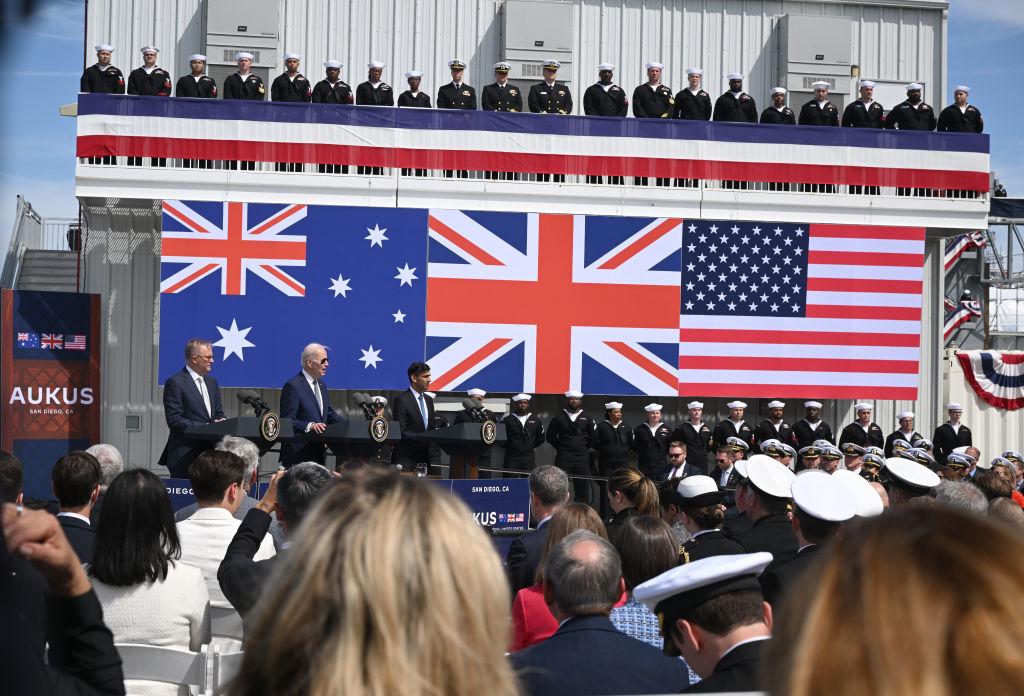

In a submission to the Senate Committee considering the trilateral AUKUS treaty between Australia, the United States, and UK, the Australia Institute outlined several concerns with the pact, and said there was a “lack of analysis and evidence in support of the AUKUS.”