Australian sextortion reports have slid for the first time since 2022. However, the Australian Federal Police (AFP) are still worried that too many victims are being blackmailed.

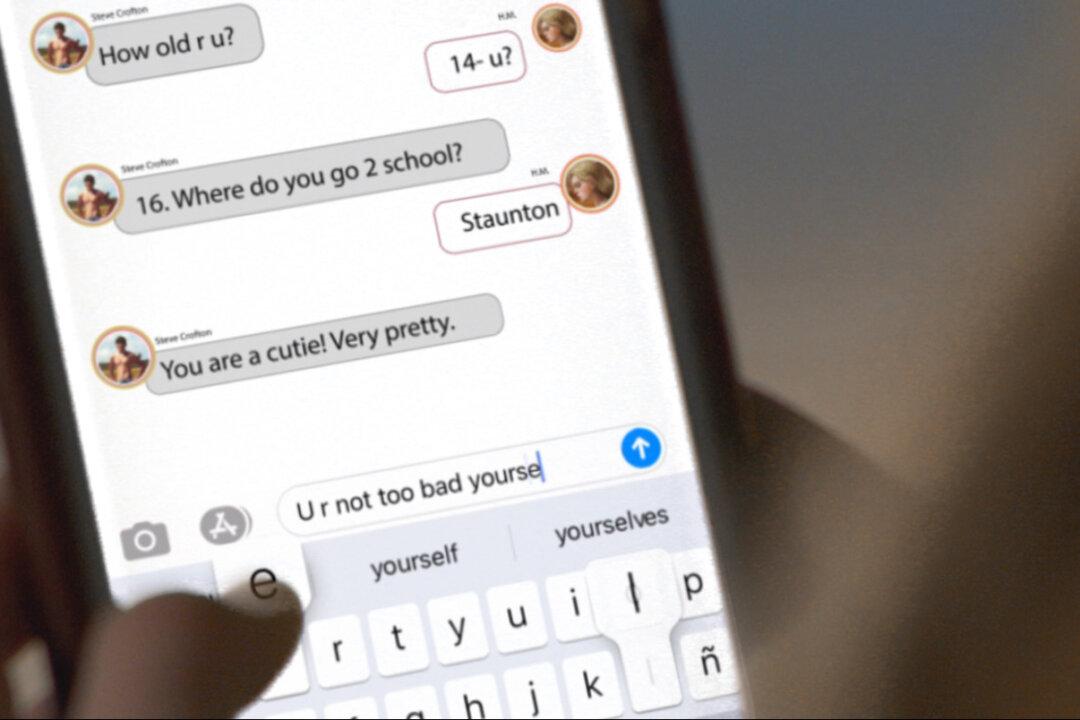

Sextortion is a type of blackmail where someone can threaten to share private and intimate images or videos unless demands are met.