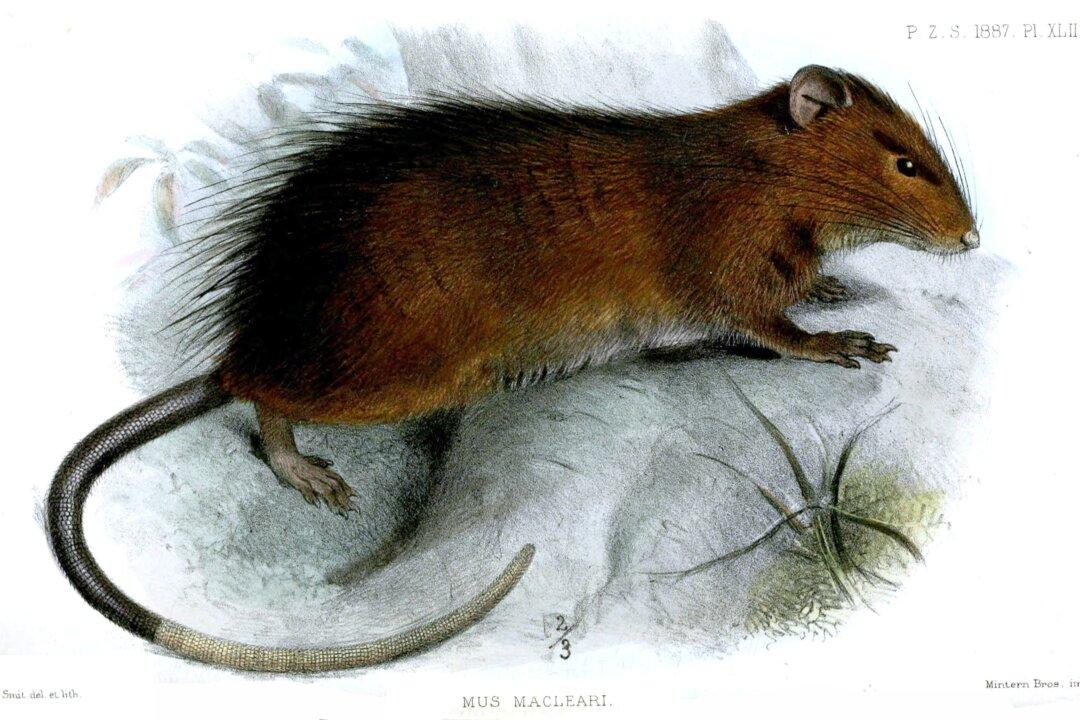

Australia’s extinct Christmas Island rat is the subject of a scientist’s exploration into the possibility of and ethics behind de-extinction.

Tom Gilbert, an evolutionary geneticist at the University of Copenhagen (UCPH) in Denmark, is attempting to reconstruct the extinct Christmas Island rat otherwise known as Maclear’s rat.