MOSCOW—A Russian organization that tracks political arrests and provides legal aid to detainees said Saturday that government regulators blocked its website, the latest move in a months-long clampdown on independent media and human rights organizations.

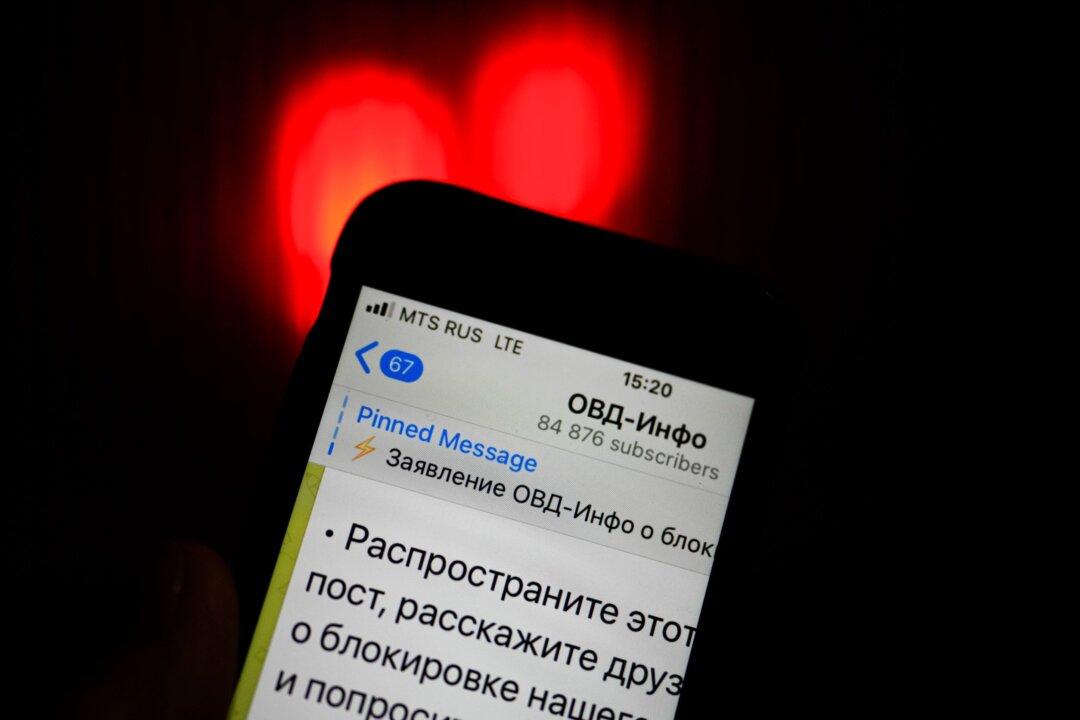

OVD-Info reported that Russia’s internet and communications watchdog, Roskomnadzor, blocked the group’s website. The organization said in a tweet that it wasn’t formally notified about the decision and doesn’t know the reason for the action beyond that it was ordered by a court outside Moscow on Monday.