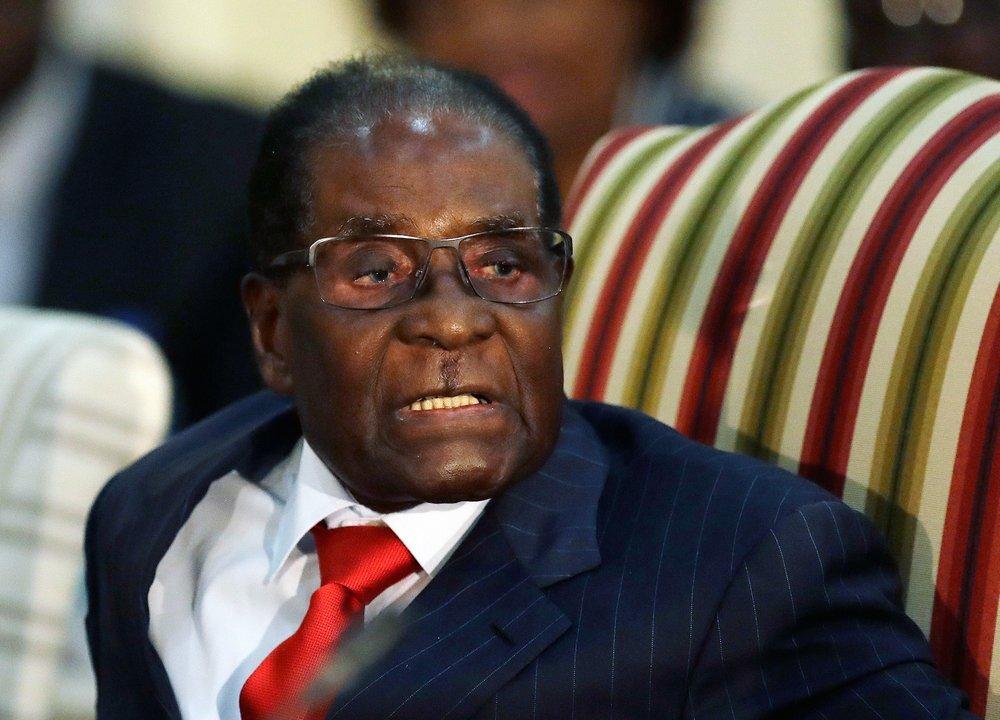

HARARE, Zimbabwe—Robert Mugabe, the former leader of Zimbabwe forced to resign in 2017 after a 37-year rule marred in its later stages by economic turmoil, disputed elections and human rights violations, has died. He was 95.

His successor President Emmerson Mnangagwa confirmed Mugabe’s death in a tweet Friday, saying, “His contribution to the history of our nation and continent will never be forgotten. May his soul rest in eternal peace.”