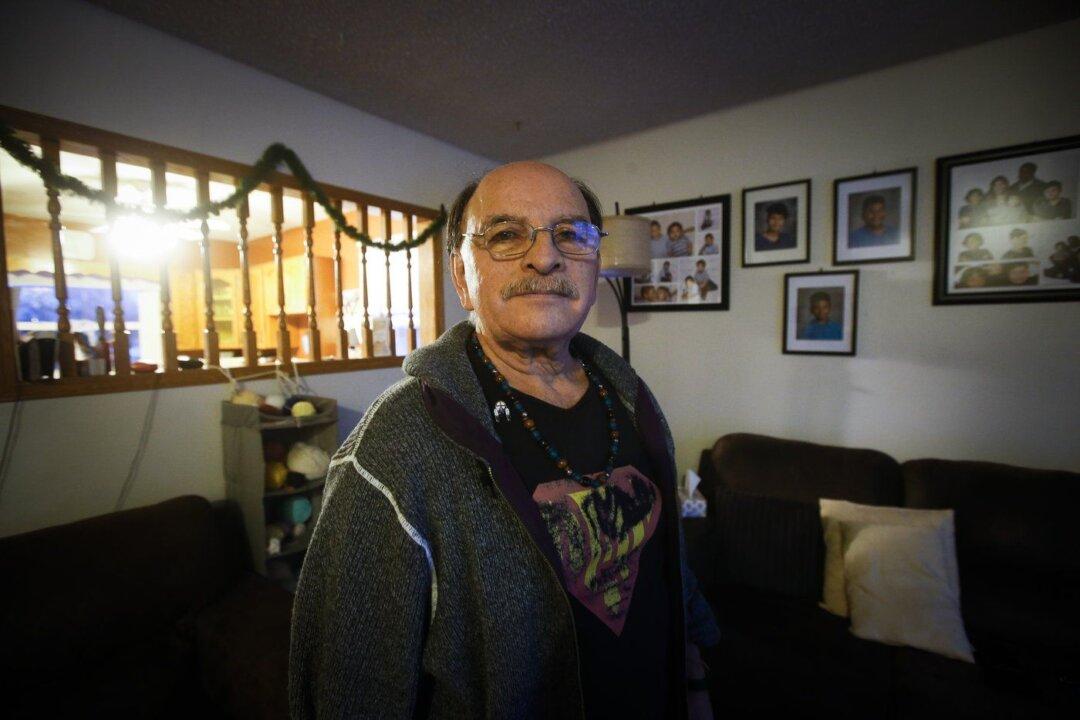

Edward Ambrose remembers wanting to be just like his father—a mentor, a hard worker, a proud family man.

More than sixty years later, Ambrose would receive shocking news. That man was not his father.

Edward Ambrose remembers wanting to be just like his father—a mentor, a hard worker, a proud family man.

More than sixty years later, Ambrose would receive shocking news. That man was not his father.