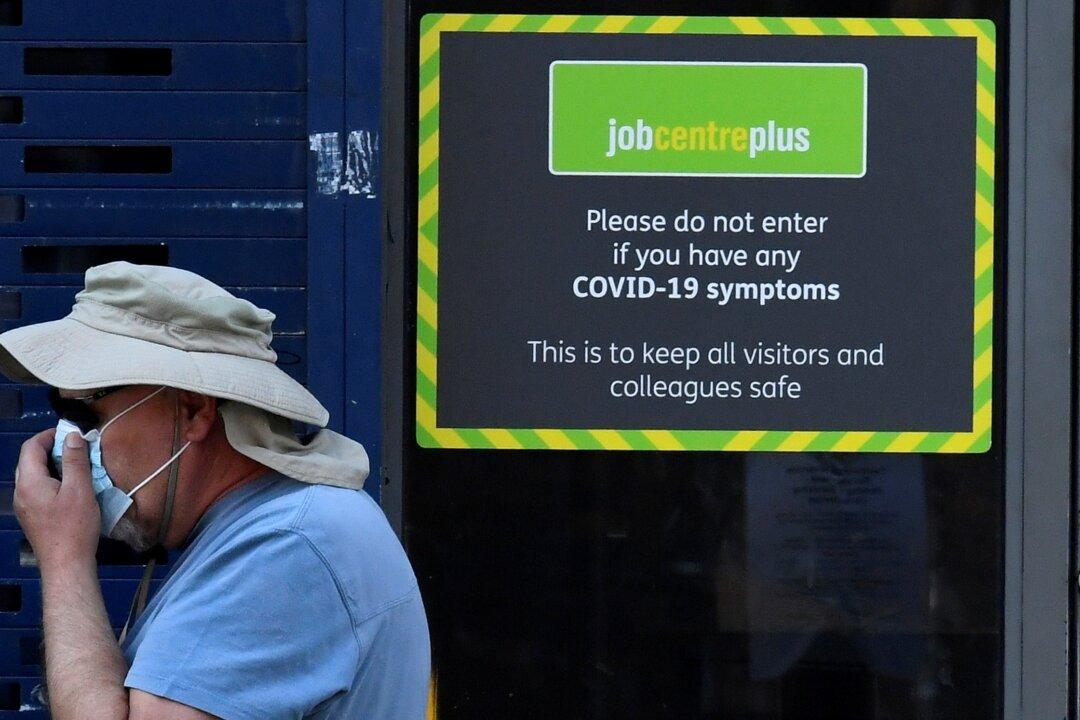

The number of people who were out of work because of long-term sickness has hit a new record, reaching almost 2.6 million, despite the government’s drive to get people back in employment.

Office for National Statistics (ONS) data published on Tuesday suggest almost half a million more people have gone out of work because of long-term illness since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.