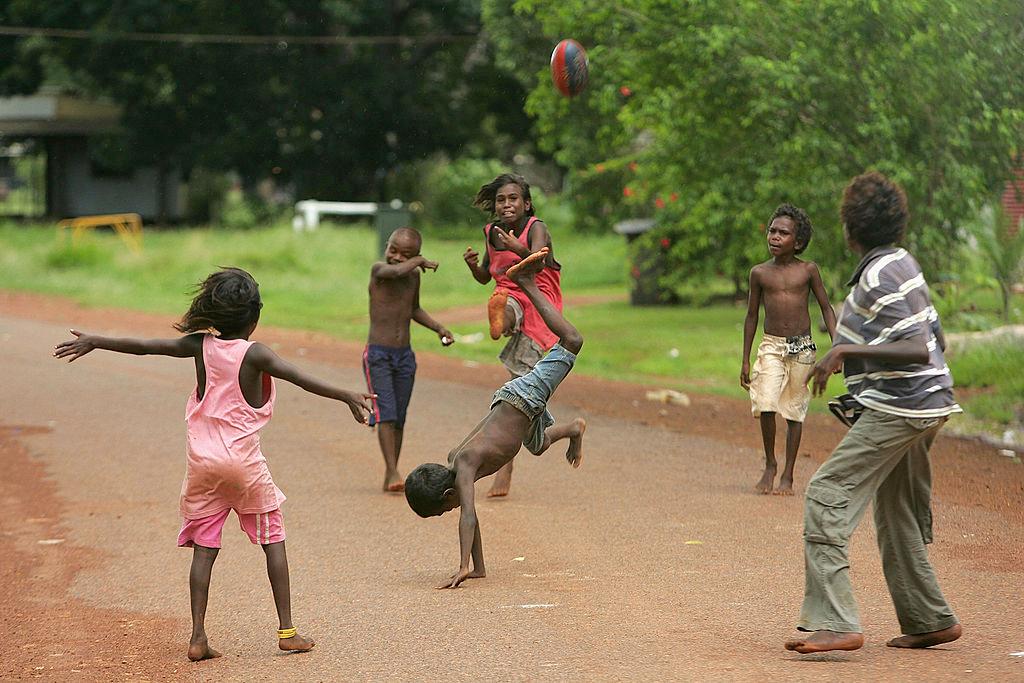

New figures show Indigenous children form a disproportionately large number of kids who have received child protection services, including for substantiated child abuse and neglect, children on care and protection orders, and children in out-of-home care.

A report released by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), titled “Child protection Australia 2019–20,” shows one in every 18 Indigenous children—or 18,900—were in out-of-home child care services as of June 30 last year.