HALIFAX—For a Halifax father and daughter dedicated to taking on global infectious diseases, the novel coronavirus has led to their latest, exhausting push to create tests and vaccines to save lives.

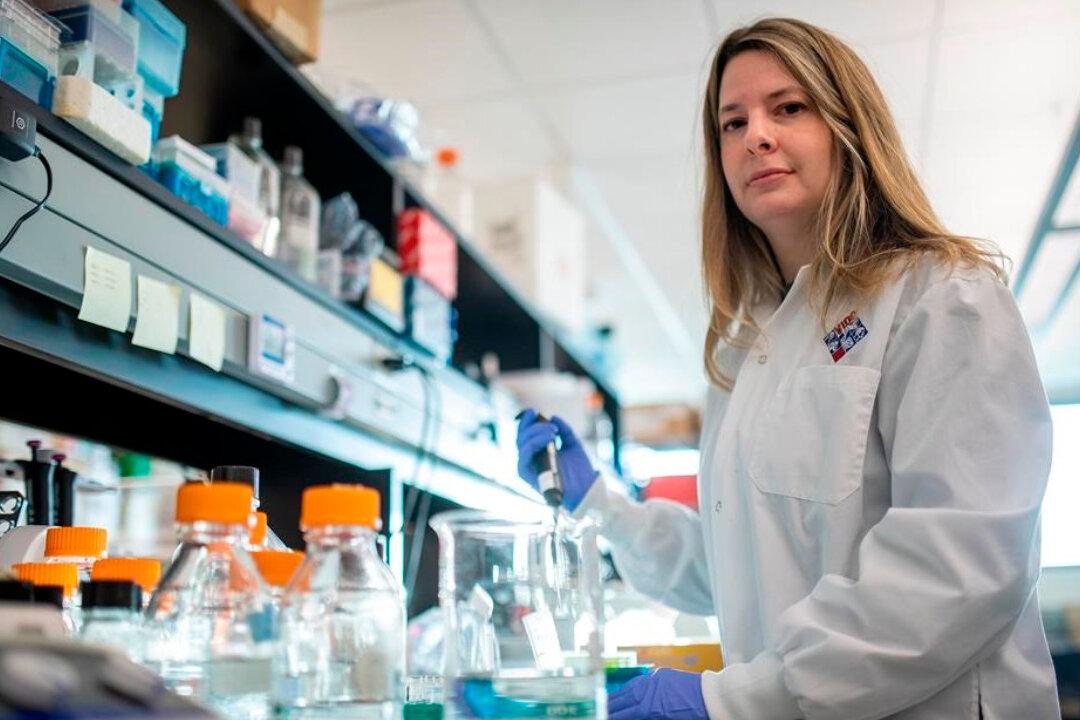

Alyson Kelvin, 39, and David Kelvin, 65, are once again in the trenches of a race to find long-term solutions, hoping for success while public interest and funding remain in place.