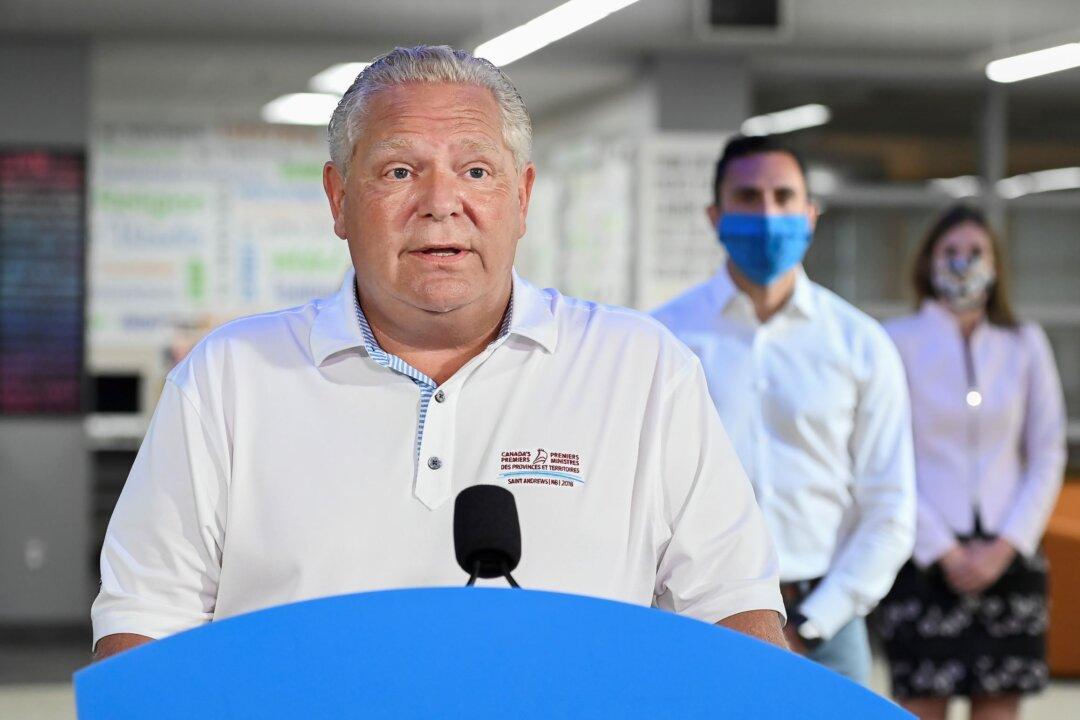

A new report on how Canada’s provinces and territories can better mitigate flood risk gives a grade of C on average to governments for flood preparedness in 2019.

The report, from the University of Waterloo’s Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation, says flooding is currently Canada’s costliest natural disaster, noting that the number and frequency of floods has increased in recent years.