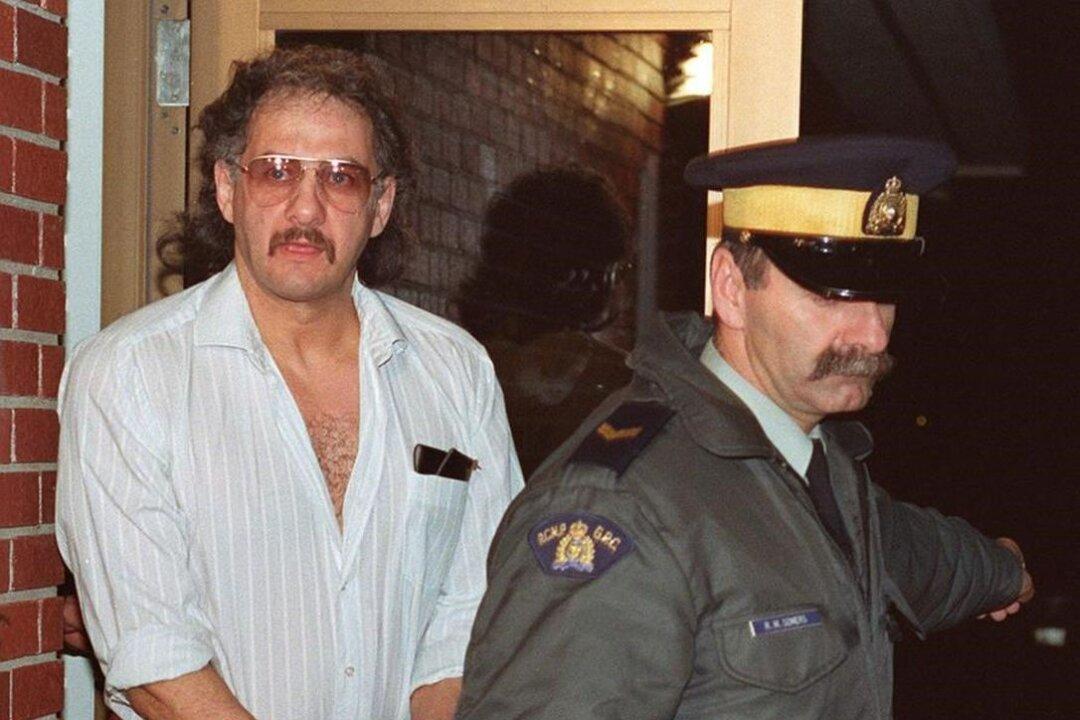

The Parole Board of Canada refused on Wednesday to release serial killer Allan Legere after hearing him blame others for the murders he committed and argue he could safely return to New Brunswick.

The convicted murderer, rapist and arsonist, who will turn 73 in February, escaped from custody on May 3, 1989, while serving a life sentence for the murder of store owner John Glendenning during a June 1986 robbery.