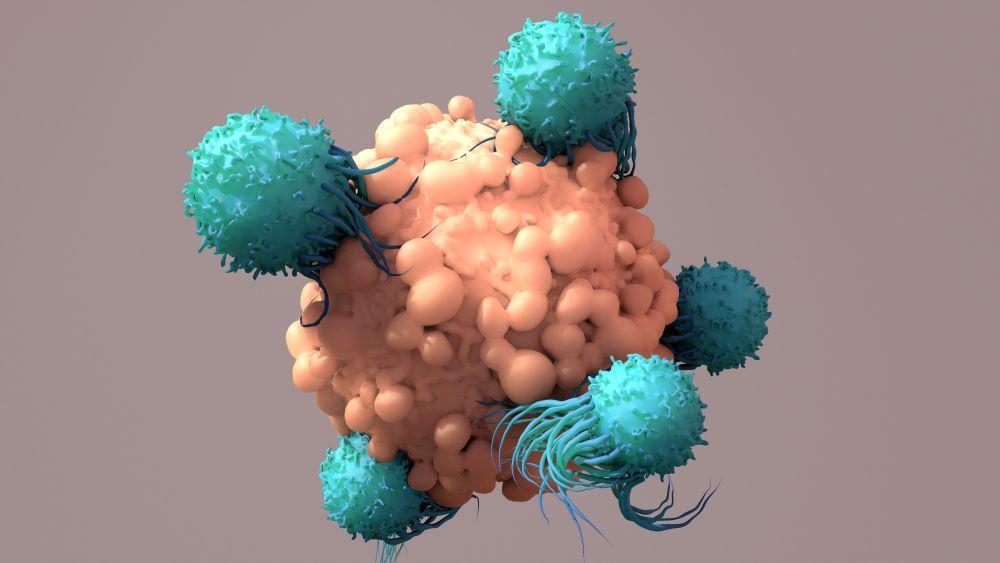

Researchers from the University of Western Australia (UWA) and Olivia Newton-John Cancer Research Institute have discovered a new way to improve response to immunotherapies in mice for the treatment of tumours.

Co-authors of the study, Associate Professor Fiona Pixley and Jay Steer from UWA’s School of Biomedical Sciences, discovered that isolating a specific molecule present in certain immune cells that hadn’t typically responded well to immunotherapy significantly improved the treatment in mice, meaning it could also potentially translate to better responses to immunotherapy in humans.