MONTREAL—The City of Montreal announced Wednesday, March 20, it will take down the crucifix that has hung in its council chamber for more than 80 years and move it to a new home.

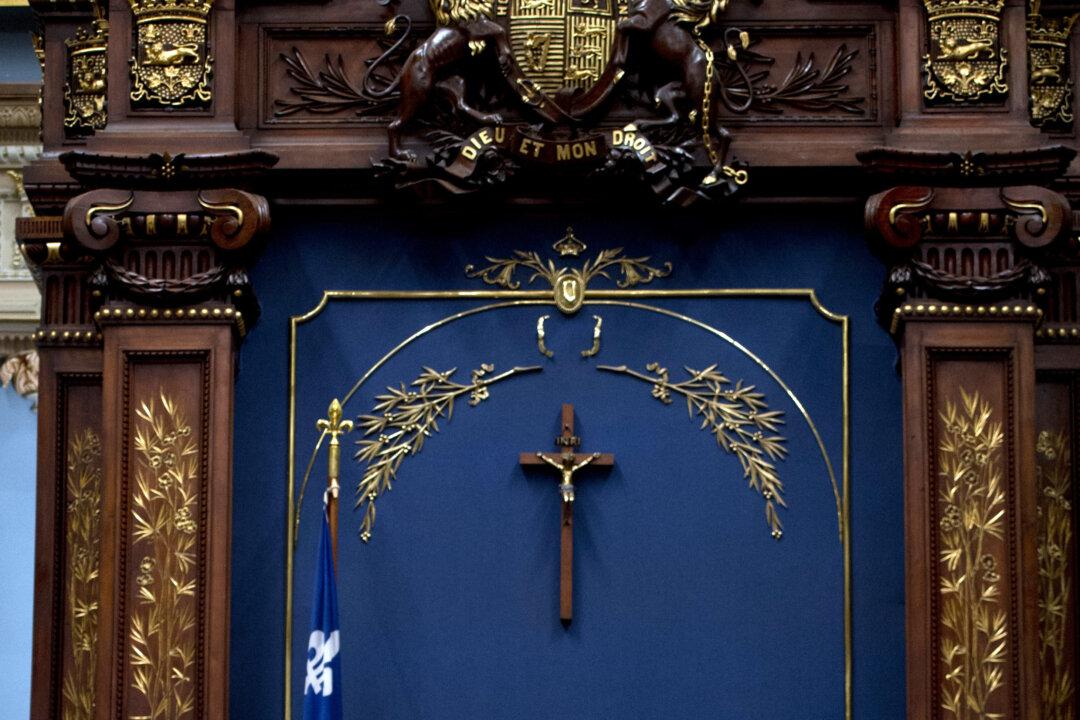

The issue of crucifixes in legislative chambers across Quebec, in particular, the one prominently displayed at the provincial legislature in Quebec City—has been central to the province’s debate over secularism.