NEW DELHI--In a village on the India-Pakistan border where cross-border shelling is a constant source of trauma, television turned into an escape route for a child into a better world.

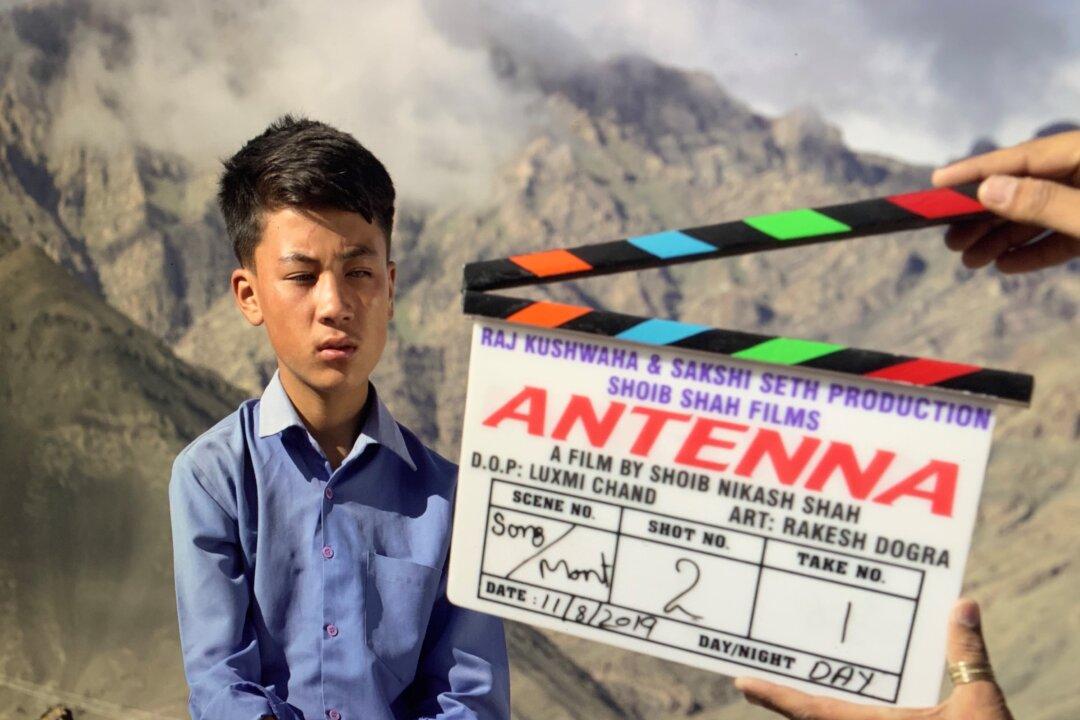

Films played on the mind of Shoib Nikash Shah so loudly that the guns outside faded into oblivion—and hence started a quest that turned a small-town dreamer into a professional filmmaker.