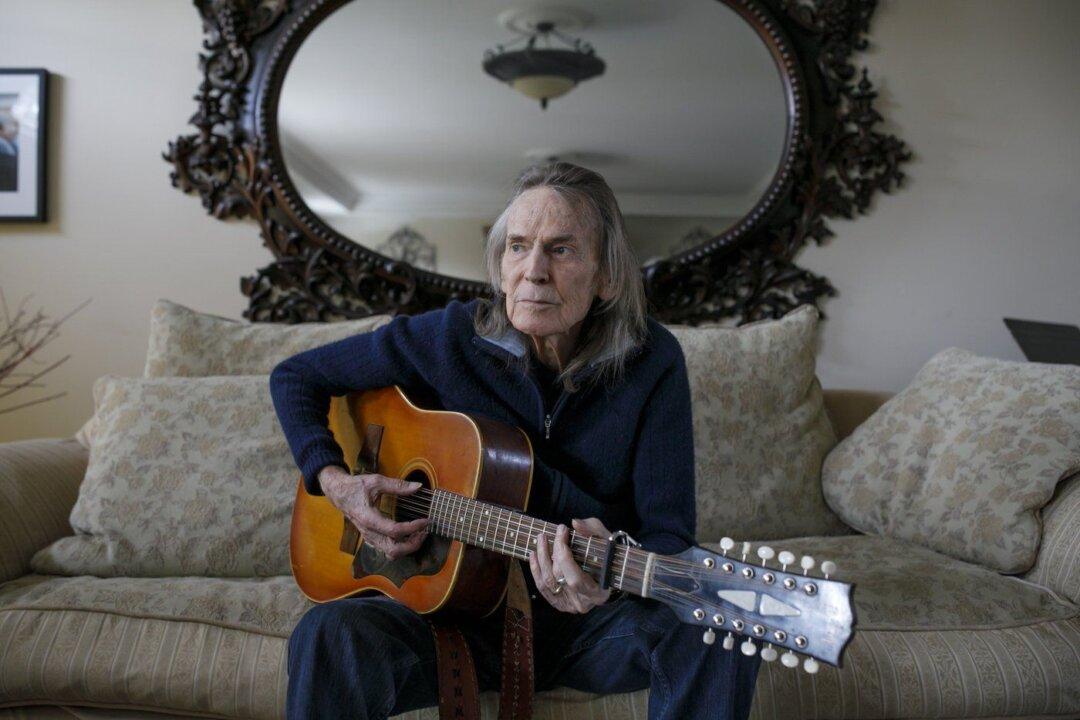

Gordon Lightfoot, the legendary folk singer whose silvery refrains told a tale of Canadian identity that was exported to listeners worldwide, has died at 84.

Lightfoot died at a Toronto hospital on Monday evening, said Victoria Lord, the musician’s longtime publicist and a representative for the family.