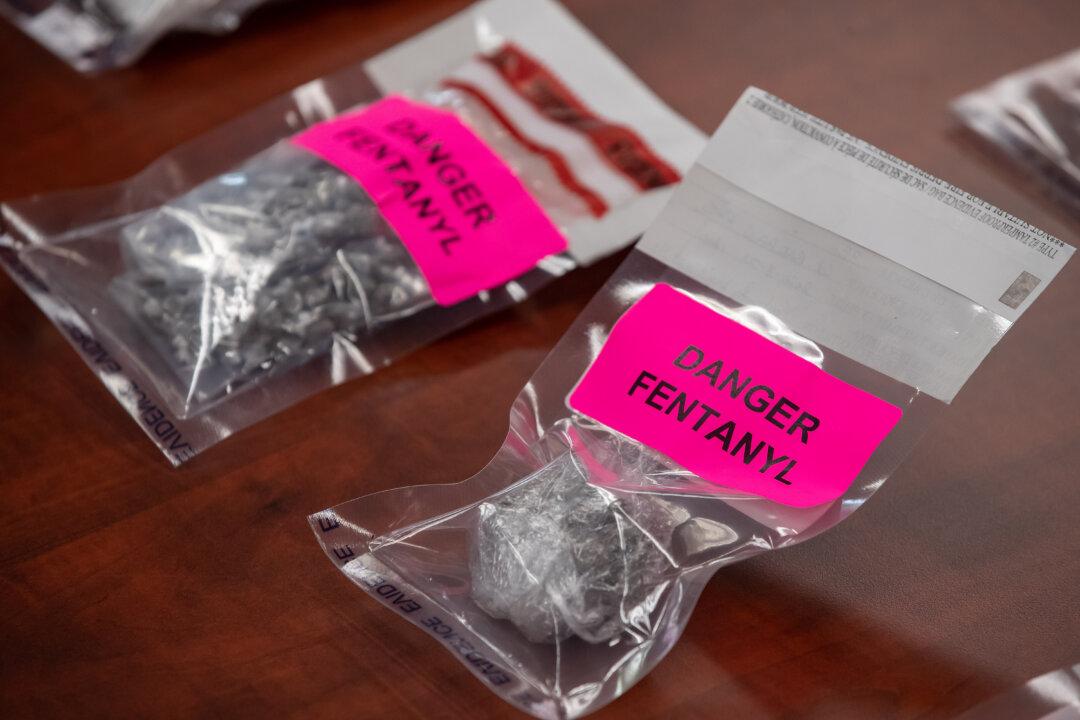

More than 1,000 people have died in British Columbia from street drug overdoses, mostly caused by fentanyl, in the first five months of 2023, according to the BC Coroners Service.

Drug toxicity from illegal drugs, which the Coroner refers to as “unregulated drugs,” is now the leading cause of death in the province in people aged 10 to 59, according to a news release issued on June 19.