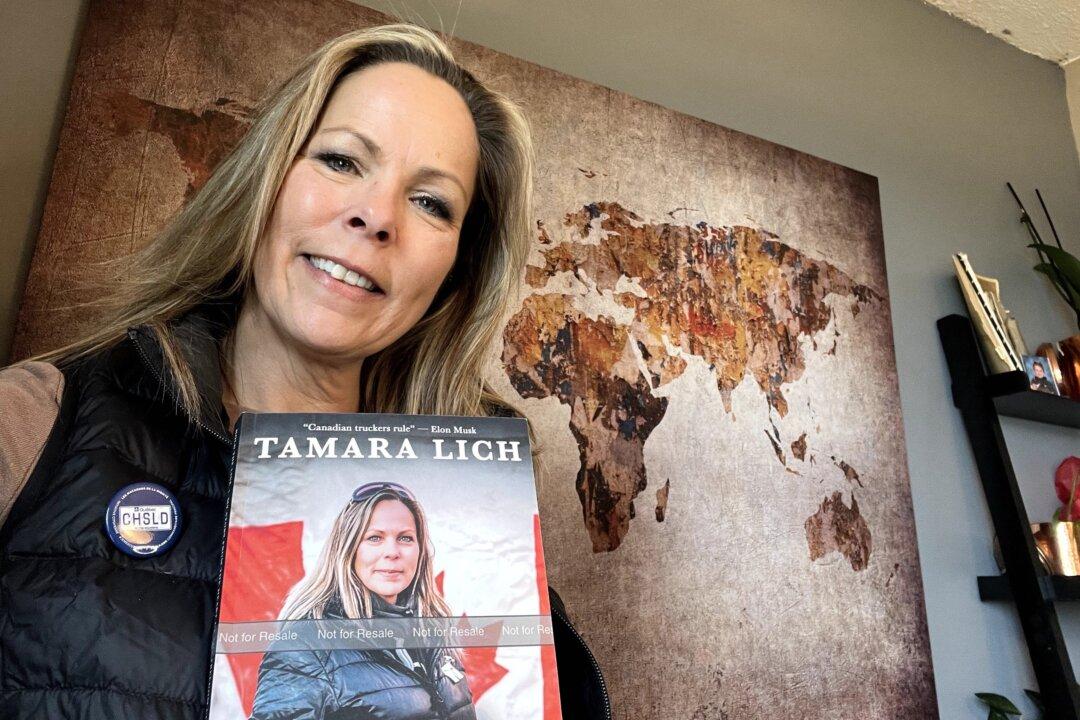

Tamara Lich, the grandmother from Medicine Hat, Alberta, who became the face of the Freedom Convoy protest, has written an autobiographical book about her journey.

“Hold the Line: My story from the heart of the Freedom Convoy,” was published on April 18. Before being released to the public, however, it was extensively reviewed by Lich’s legal team given that she faces mischief charges related to the convoy.