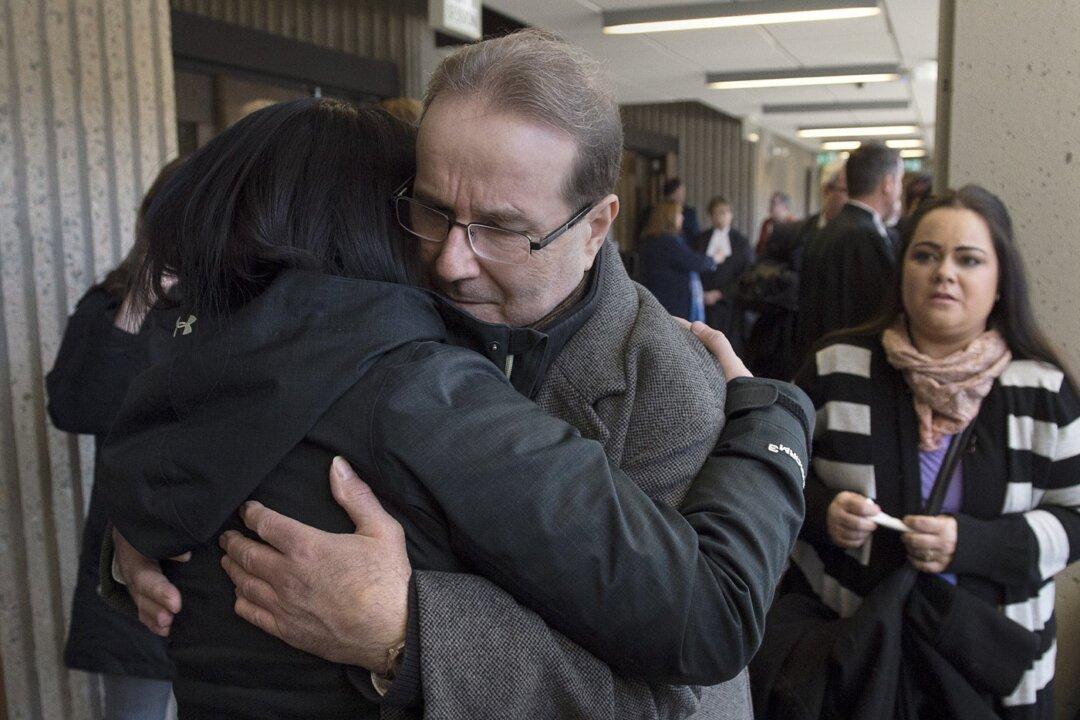

The daughter of a wrongfully convicted Nova Scotia man says that even in death her father is being denied justice—and she is demanding a stalled criminal investigation of his case become “a priority.”

Amanda Huckle says that she and her family were deeply frustrated when they learned last month that a police oversight body had stopped its three-year probe to determine whether RCMP officers broke the law when they destroyed evidence in the case that led to the conviction of her father, Glen Assoun, for murder.