Highly potent opioids such as fentanyl are being produced by pharmaceutical companies, paid for by Canadian taxpayers, and given out as part of “safer supply” programs.

Following Canada’s Safe Supply Money—From Taxpayer to Pharmaceutical Companies

Drugs provided under “safer supply” programs are produced by companies who have been taken to court in relation to the opioid addiction crisis.

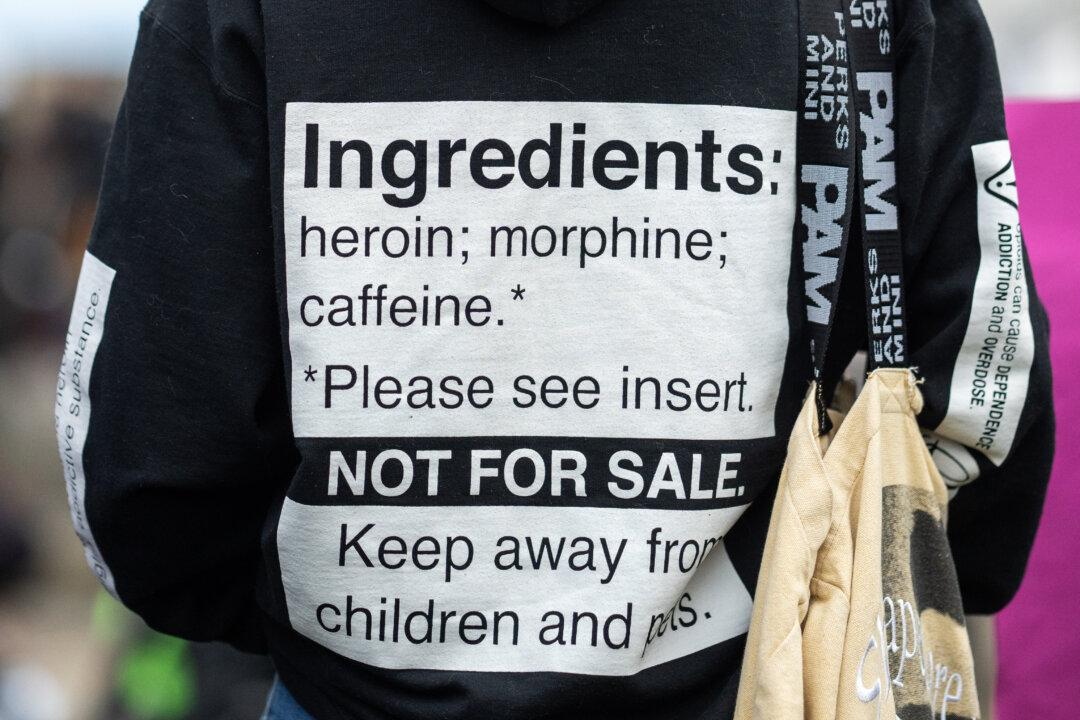

A person with a sign on his hoodie takes part in a pro-safer supply demonstration in Vancouver on Nov. 3, 2023. The Canadian Press/Ethan Cairns

|Updated: