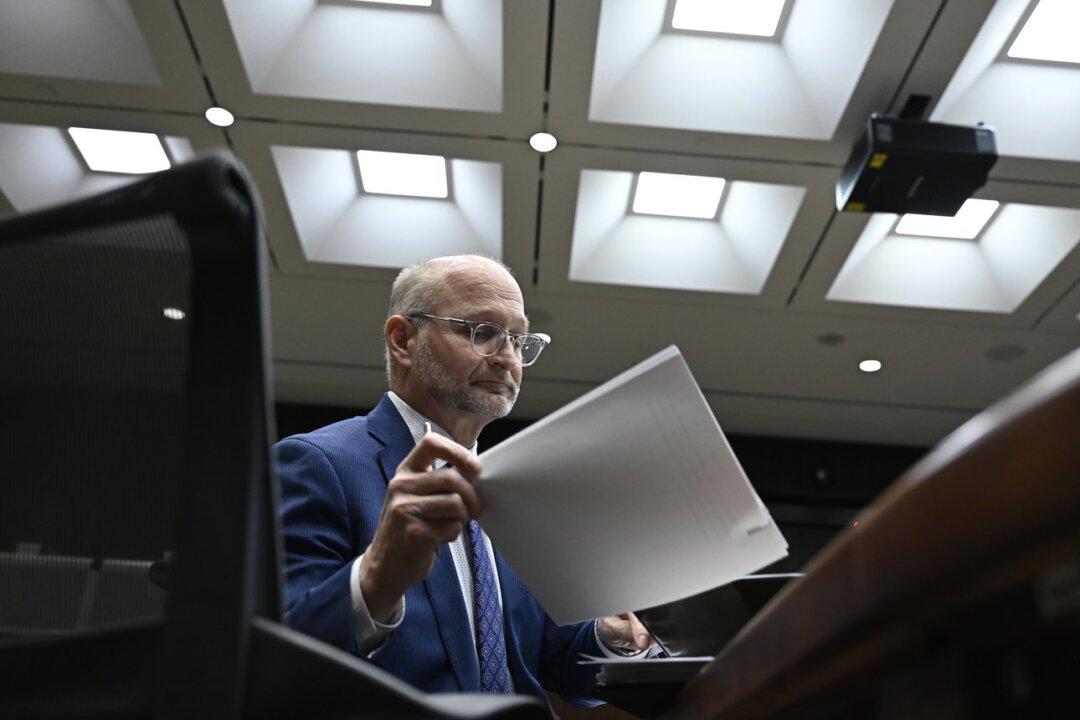

Justice Minister David Lametti is preparing to face off with his provincial counterparts in Ottawa Friday on whether to reform Canada’s bail system, as premiers, federal Conservatives and law enforcement leaders demand more restrictions.

But while he has signalled an openness to reform, Lametti has also cautioned that more-restrictive laws could bump up against the Charter of Rights and Freedoms—and experts warn there are already too many innocent people awaiting trial behind bars.