OTTAWA—Although the topic at a House of Commons foreign affairs committee hearing on April 24 was “Canada’s Engagement in Asia,” most of the witnesses focused their testimony on China.

Pitman Potter, a professor at the University of British Columbia’s A. Allard School of Law, said it’s important for Canada to understand that the rule of law in China—or the absence thereof—means something very different from that in this country.

Testifying via video conference, Potter said that for Canadians, the rule of law means things like the protection of citizens’ rights and limitations on government action, but the rule of law in China is a “Socialist rule of law” established by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

“What is described in China as the rule of law is more, in fact, the rule by law—in other words, the use of formal rules, statutes, institutions, and so on to carry out policies,” Potter explained, adding that China’s rule of law “is nothing more than an instrument for carrying out Party purposes.”

This, in effect, is an absence of the rule of law.

“So when I think about what the implications of this are for Canada, it’s important to note that this is not simply a domestic matter. This affects China’s treaty compliance, China’s respect for its own laws, its respect for international treaties, and things like human rights, ethnic minorities, and trade,” he said.

“So the absence of the rule of law in China affects all aspects of Canada’s relations with China.”

Transplant abuse

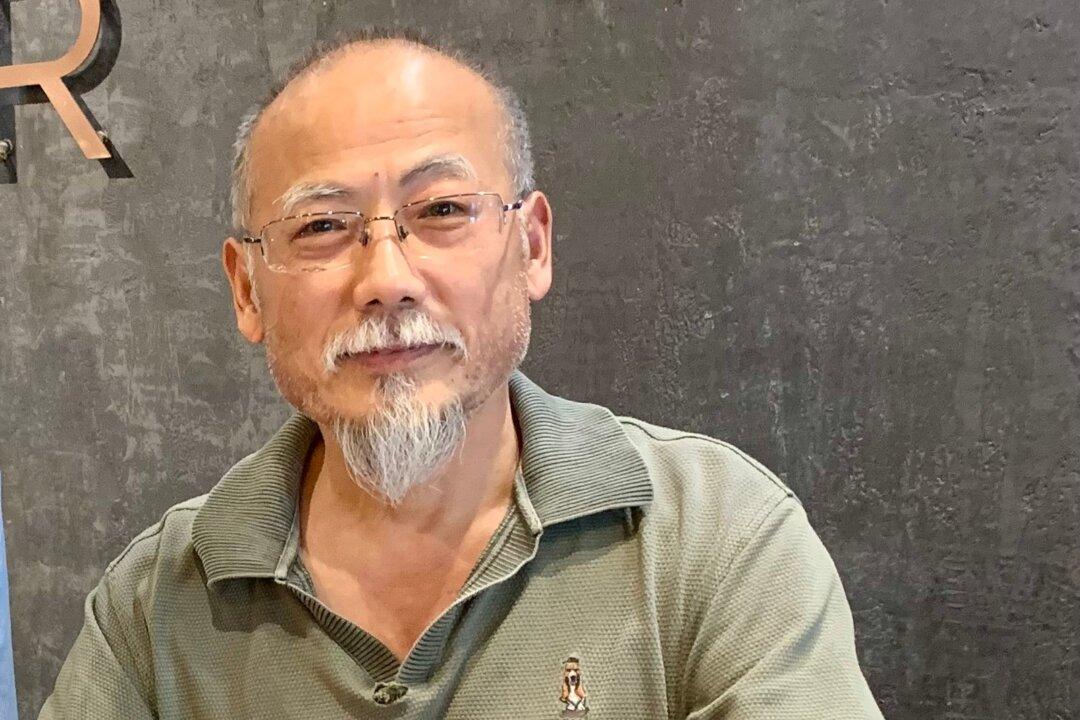

Winnipeg-based international human rights lawyer David Matas, who was present at the hearing, began his testimony with this question: “What form should engagement of Canada with China take in light of the evidence of organ transplant abuse in China?”Matas went on to explain his work with former MP David Kilgour to expose the crime of forced organ extraction from Falun Gong prisoners of conscience in China.

He noted that since he and Kilgour released their first report 12 years ago, evidence has accumulated and other researchers have engaged the issue, including U.S. investigative journalist and China expert Ethan Gutmann.

“A joint report with Gutmann released in June 2016 found that the volume of transplants in China was up to 100,000 a year, and that the bulk of the sources were prisoners of conscience—Tibetans, Uighurs, house Christians, and primarily practitioners of Falun Gong,” Matas said.

“The evidence of this abuse, by now, is overwhelming,” he said, noting that “the abuse is a black market with an unusual feature—it is institutionalized, state-run.”

Matas said that when it comes to engagement with China, “the mass killing of prisoners of conscience for their organs cannot just be put to one side. … Engagement with China calls for engagement on this issue.”

He made several suggestions on what Ottawa can do to help curb forced organ harvesting, including acting on statements endorsed by the Subcommittee on International Human Rights in 2013 and 2015.

“Both statements called on medical and scientific professional and regulatory bodies to name, shame, and ostracize individuals, institutions, and their affiliates involved in the forced harvesting and trafficking of human organs,” Matas said.

“Right now there is an active debate within the international transplant profession about whether to engage or ostracize the Chinese transplant profession in light of the Chinese official opacity about transplantation and the overwhelming evidence of continuing transplant abuse” Matas noted.

“I support ostracism, as the subcommittee did, because engagement removes the lever of peer pressure which, historically, when there has been ostracism, has had an impact. The government of Canada should be supporting the voices for ostracism as the subcommittee did.”

Matas also said Canada should call on Beijing to cooperate with an independent international investigation into organ transplant abuse in China.

The ‘China Dream’

The others who testified were Charles Burton, an associate professor of Political Science at Brock University; Paul Evans, interim research director of the Institute of Asian Research and a professor at the Liu Institute for Global Issues at UBC; Ngodup Tsering with the Office of Tibet in Washington, D.C.; and Chen Yonglin, a former Chinese diplomat who defected to Australia in 2005.Speaking via video conference, Chen noted that China has ambitions to become the world’s superpower by 2049, in keeping with Party leader Xi Jingpin’s initiation of “China Dream 2049.”

Beijing has become “more aggressive” in working to achieve that, he said.

“In the last 25 years, the Chinese authorities have silently infiltrated major Western democracies, including Australia and the U.S. Australia has been a testing ground for China’s soft power, which has had great success.”

Chen referred to the book “Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia,” an exposé of the CCP’s extensive infiltration of Australia written by Clive Hamilton.

“It is almost too late for Australia to defend itself against China’s interference,” Chen said.

“In the eyes of the Chinese authorities, Canada is in a similar position to Australia. … Both countries are seen as weak links in the Western democracy alliance, where China can snitch high tech and exert influence.”

Chen said China has exercised its overall diplomacy with Canada since the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, noting that Canada was the first Western country “to decouple its human rights policy from its trade policy.”

He also noted that “the appeasement of Western countries helped China join the WTO without completely fulfilling its obligations. That enabled China’s economy to benefit from free trade without making the slightest move towards democracy,” he said.