Emerging from Chicago’s South Side, drill music is known for its dark and violent lyrics that often reflect the harsh realities of gang life.

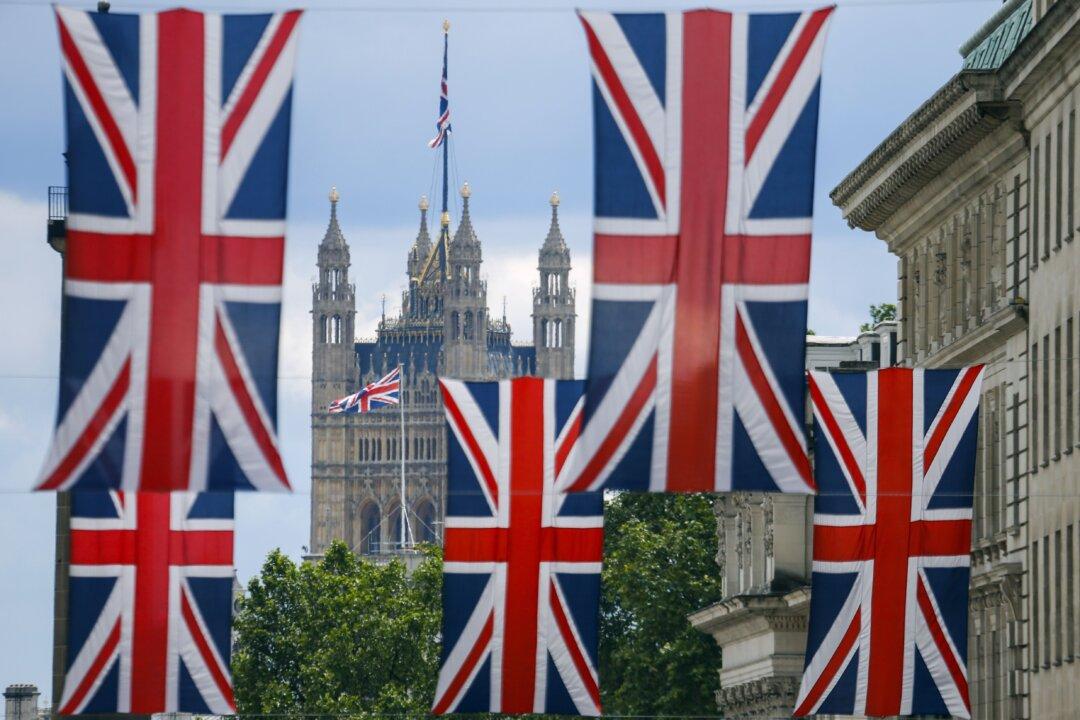

Like grime in the 2000s, drill rap has become a controversial topic in the UK music world, with London police associating the hip-hop subgenre to the recent surge of violent crime in the capital.