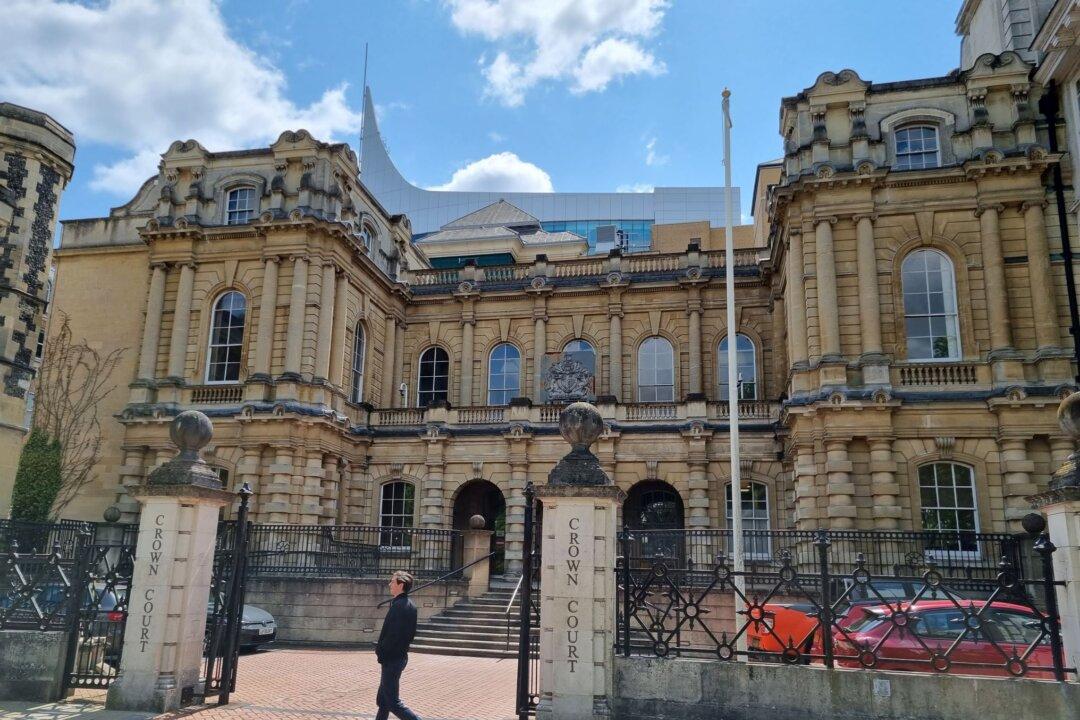

The record-high backlog of criminal cases in crown courts will keep growing unless the government makes major policy changes, a senior official has warned.

Speaking to the Commons Public Accounts Committee (PAC) on Thursday, MoJ Permanent Secretary Antonia Romeo said this number will continue to grow.

“Our modelling indicates that—absent significant additional policy changes or changes to the system—the number will be higher than it is now,” she said.

The current caseload has risen by 3 percent compared to the previous quarter and is 10 percent higher than the same time last year, when 66,426 cases were pending.

This figure is nearly double the 38,016 cases outstanding at the end of 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic began.

The pandemic then led to a significant increase in the caseload up to about 58,000 in March 2022. Romeo told the committee that ministers planned to reduce the caseload down to 53,000 by March 2025, but conceded that instead the figure rose to record-high levels.

“I’m not suggesting that this is a temporary problem. The problem is that the demand coming in is not being met. We do not have the ability to dispose of the cases that are coming in at the rate that they’re coming in,” Romeo said.

She explained that in addition to the impact from pandemic restrictions, the growing backlog was affected by the criminal barristers’ strikes in 2022.

Reforms

The rising backlog prompted the government to commission a review of the courts system in December, led by retired judge Sir Brian Leveson. The review aims to explore solutions for alleviating pressure on crown courts and improving overall efficiency.One of the key proposals under consideration is the introduction of intermediate courts, designed to handle cases that are too serious for magistrates’ courts but not severe enough for crown courts.

These cases would be heard by a judge and magistrates, rather than a jury, which could help speed up case resolutions.

The review will also examine whether magistrates should be granted extended sentencing powers. This would allow magistrates to issue longer and tougher sentences, enabling them to handle more cases and free up crown court judges to focus on the most serious and complex crimes.

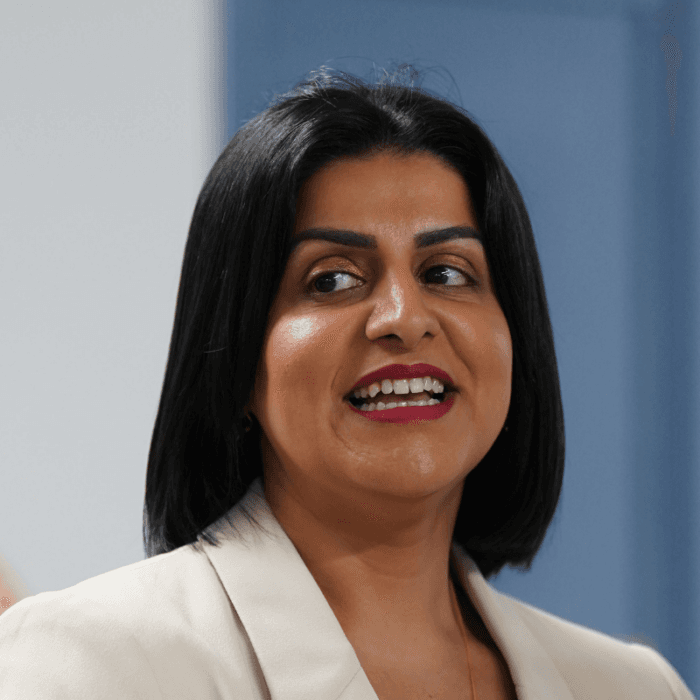

Justice Secretary Shabana Mahmood has suggested that Labour inherited an “unprecedented” scale of crown court crisis from the previous government. She highlighted the impact of delays on victims, who are often “waiting years to see their perpetrator put before a judge.”

“We owe it to victims to find bold, innovative approaches that will speed up justice, deliver safer streets and send a clear message to criminals that they will quickly face the consequences of their actions,” she said.

Looking Ahead

The Leveson review is expected to issue preliminary recommendations in the spring, around the same time former Justice Secretary David Gauke’s sentencing review will be considered by ministers.Gauke will also examine ways to combine punitive measures with effective rehabilitation programs to reduce reoffending rates.

An open call for evidence launched on Nov. 15 highlights examples such as a Texas prison programme where inmates can reduce their time before release by participating in rehabilitative activities. This model will be assessed as part of efforts to create more effective sentencing strategies.