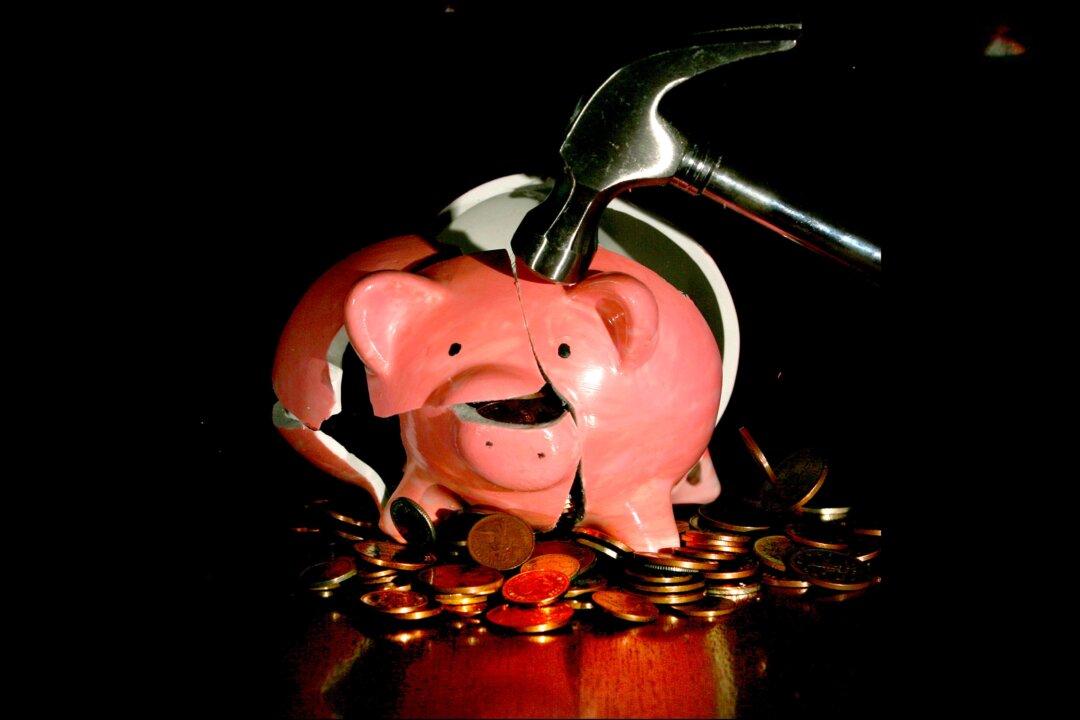

Bad management, rather than a shortage of money, is the reason why councils have been effectively going bust, according to the local government watchdog.

Lord Morse, chairman of the Office for Local Government (Oflog) said on Wednesday that councils “have to be realistic” about how much support they can expect to get from Westminster.