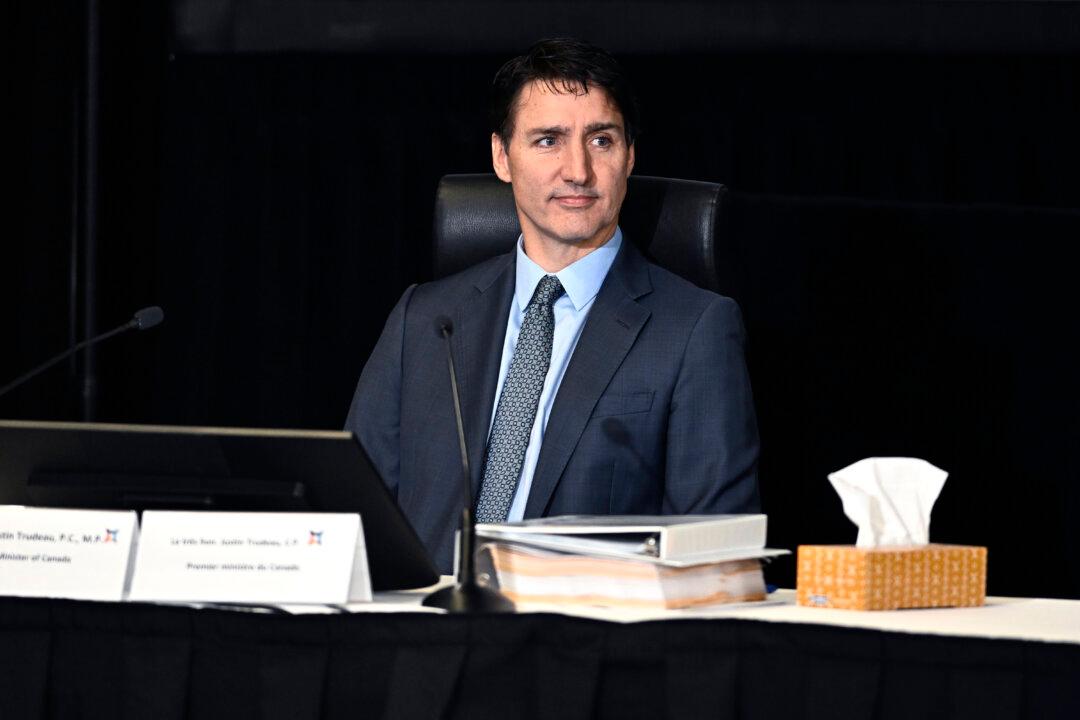

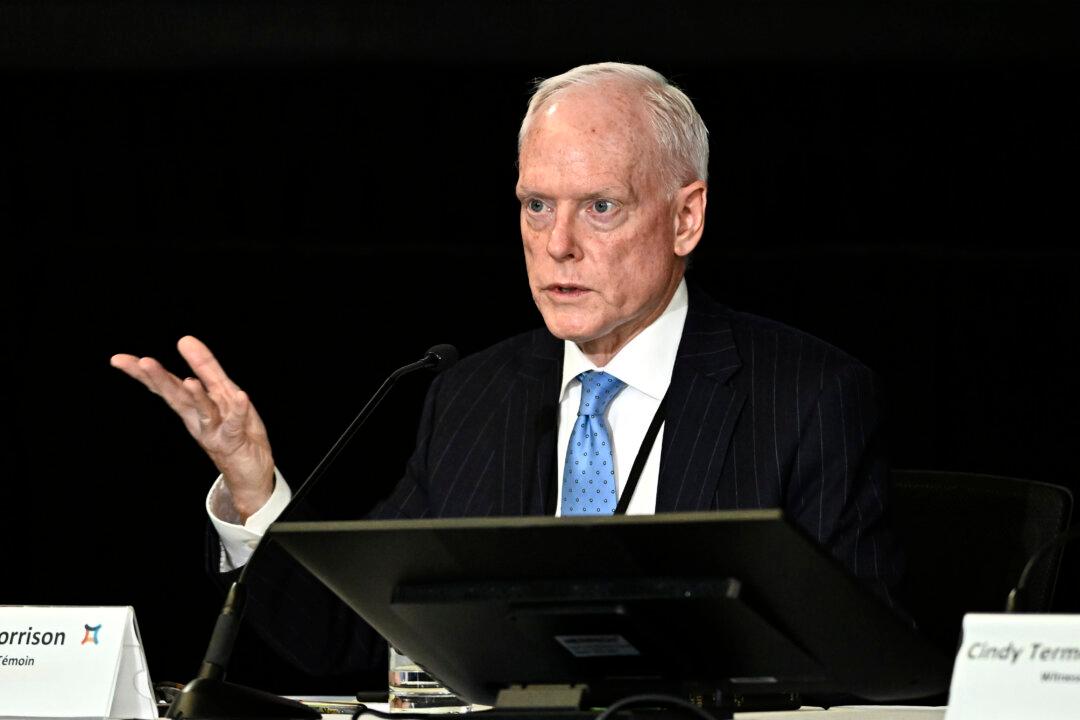

The final phase of public hearings at the Foreign Interference Commission concluded this week, leaving several stones unturned regarding specific issues such as a delayed surveillance warrant and around broader issues such as what actually constitutes foreign interference.

Tensions within the federal government were on display during the hearings, as diplomats and top officials pushed back against Canada’s spy agency on what can be considered a threat to national security.