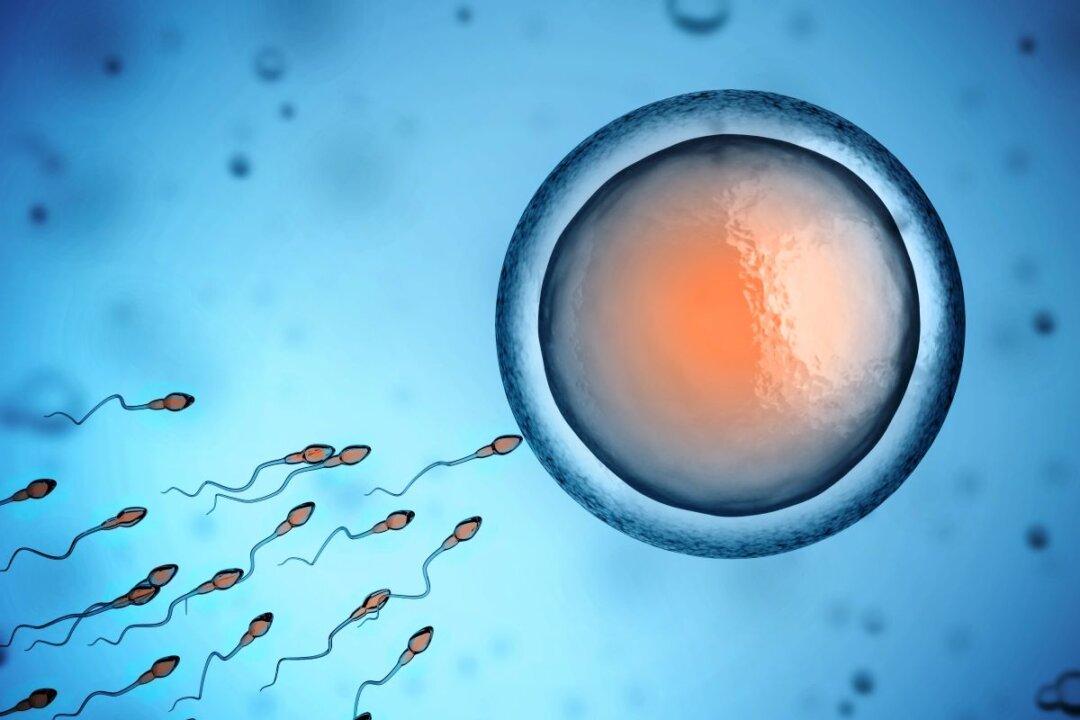

Australian researchers have found that some immunotherapy treatments for cancer can damage fertility, prompting a call for further research and preventative measures such as freezing eggs.

A pre-clinical trial, led by experts from Monash University’s Biomedicine Discovery Institute and the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, demonstrated that a common type of immunotherapy drug known as immune checkpoint inhibitors led to the permanent damage of mouse ovaries and the eggs within.