Australian soldiers dispatched to the Solomon Islands last year after violent riots razed parts of the capital Honiara to the ground admitted to Heston Russell, a former special force operative, that they were “providing security for the Chinese.”

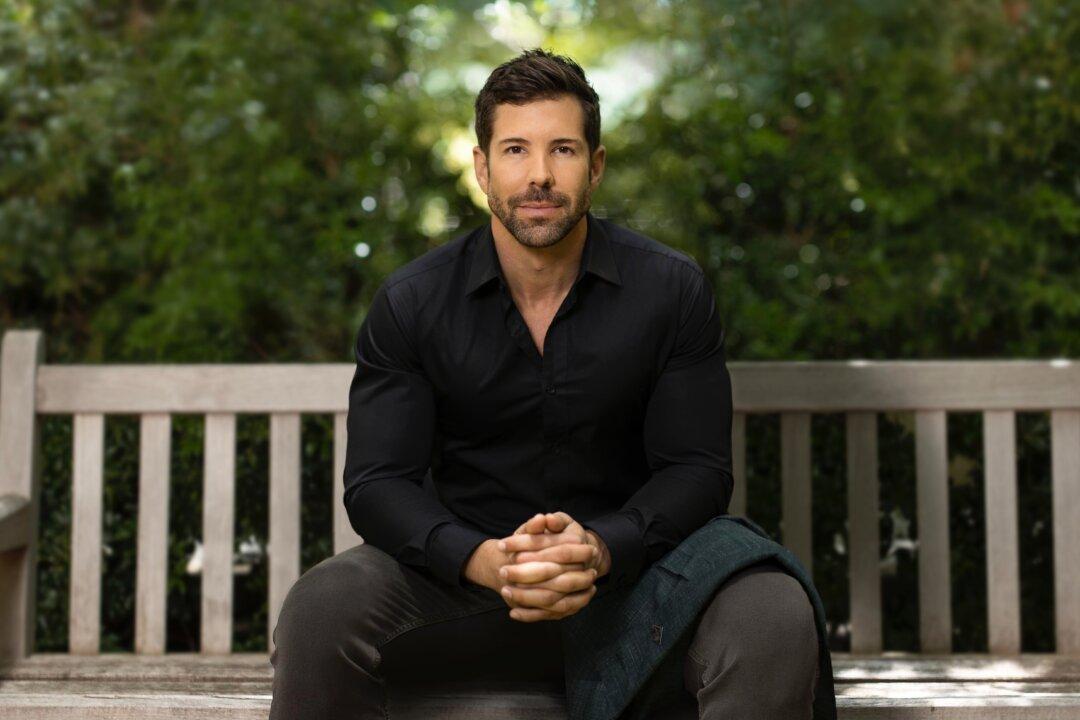

“They said to me, ‘We didn’t know what we were doing there because the people of the Solomon Islands were rioting against a government that had accepted money from the Chinese to recognise Taiwan as Chinese territory,’” according to Russell, an advocate for veteran affairs and now the Queensland Senate candidate for the Australian Values Party.