Geopolitical tensions in the Red Sea are placing pressures on Australia’s agricultural sector through the disruption of international supply chains, according to agribusiness banking company Rabobank.

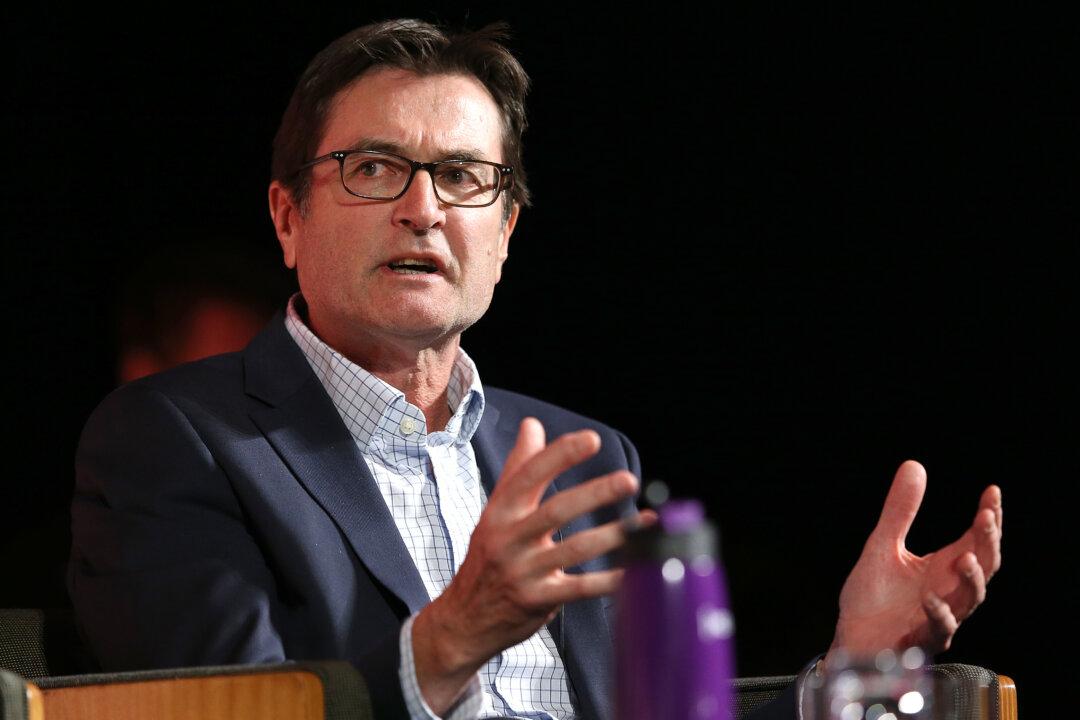

RaboResearch general manager Stefan Vogel is particularly concerned about Australian canola exports, given that the majority are shipped to Europe through the Suez Canal.