Canada’s defence spending has come under the spotlight with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but experts say the issue is more complicated than simply meeting the NATO benchmark of 2 percent GDP to solve the issue.

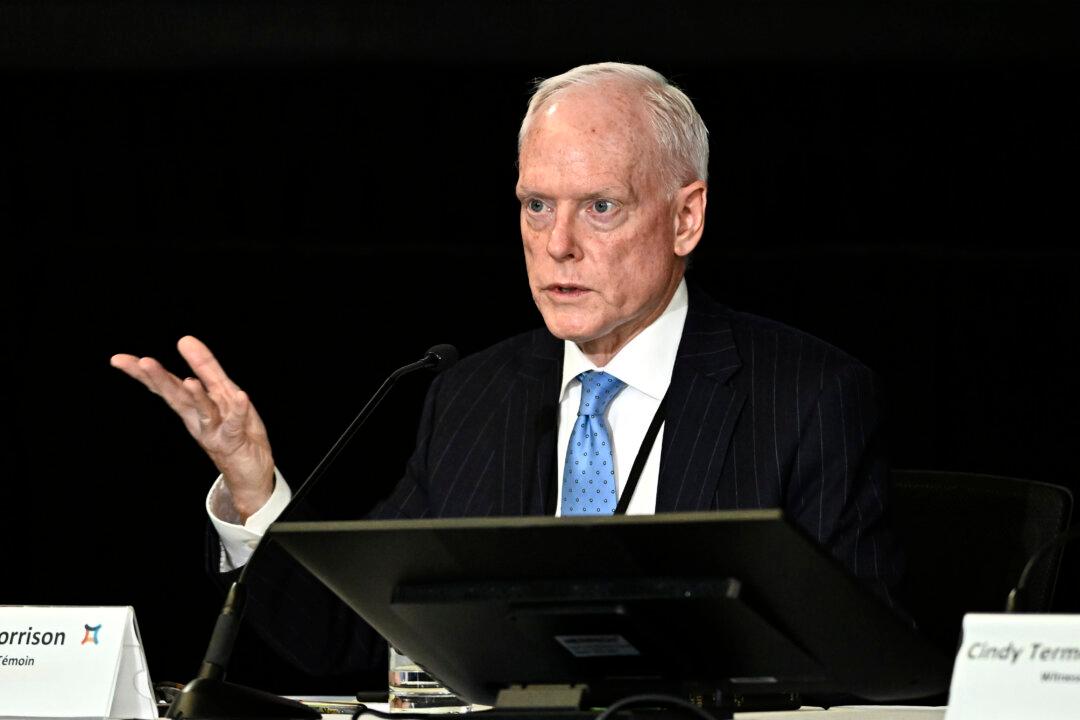

For the experts testifying before the Standing Committee on National Defence on March 21, increasing the budget without a defence review and an articulated strategy will not solve Canada’s military deficiencies.