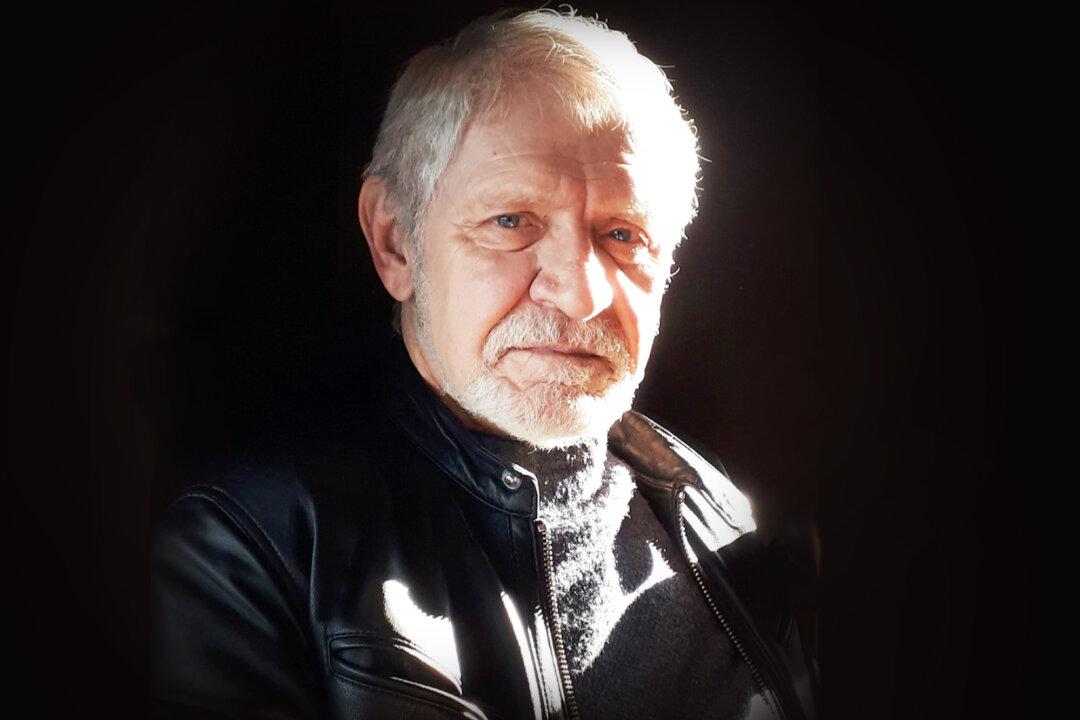

Frank Licsko’s life began behind the Iron Curtain in Soviet Hungary, but he escaped communism for freedom in the West, where he went on to become a professional artist.

Licsko, who now lives on Vancouver Island in B.C., just completed a two-metre homage to American liberty whose centrepiece is Lady Liberty herself. He says what it expresses is something his father would have been killed for expressing in his once-communist homeland.