A new model by Dalhousie University’s food analytics lab has forecasted that compared to 2022, wholesale food prices in Canada, before goods are sold to grocers, will rise by 34 percent on average for all food categories by 2025.

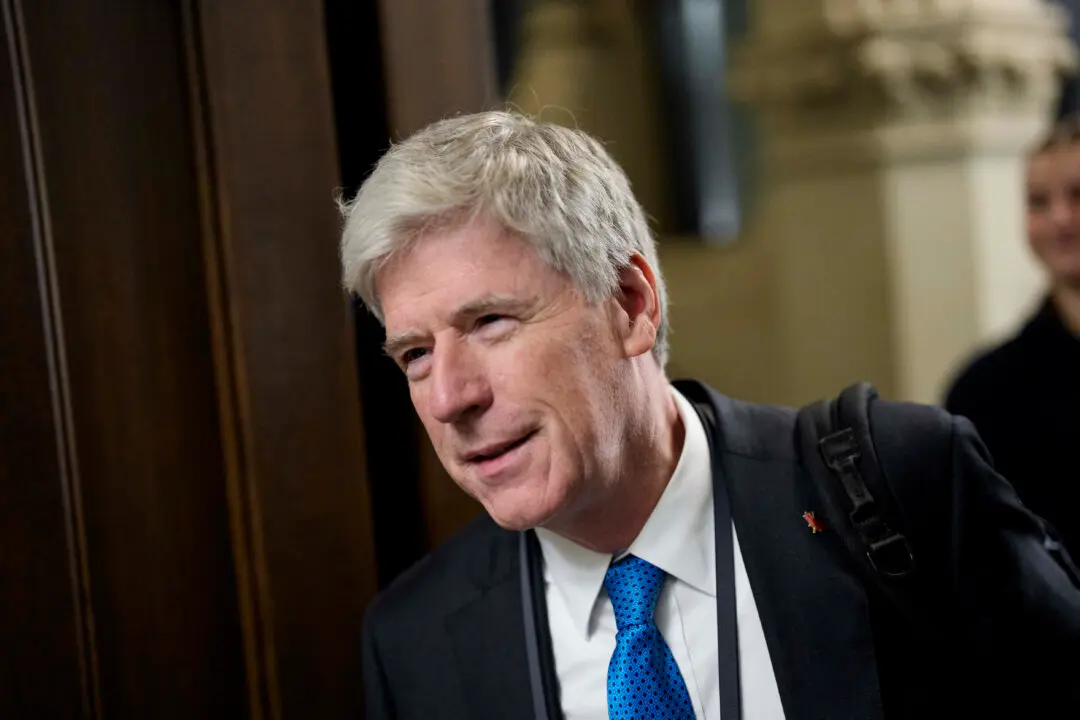

“It’s going to be quite problematic and I think we need to be ready for this,” Professor Sylvain Charlebois, senior director of the Agri-Food Analytics Lab, told The Epoch Times on April 19.