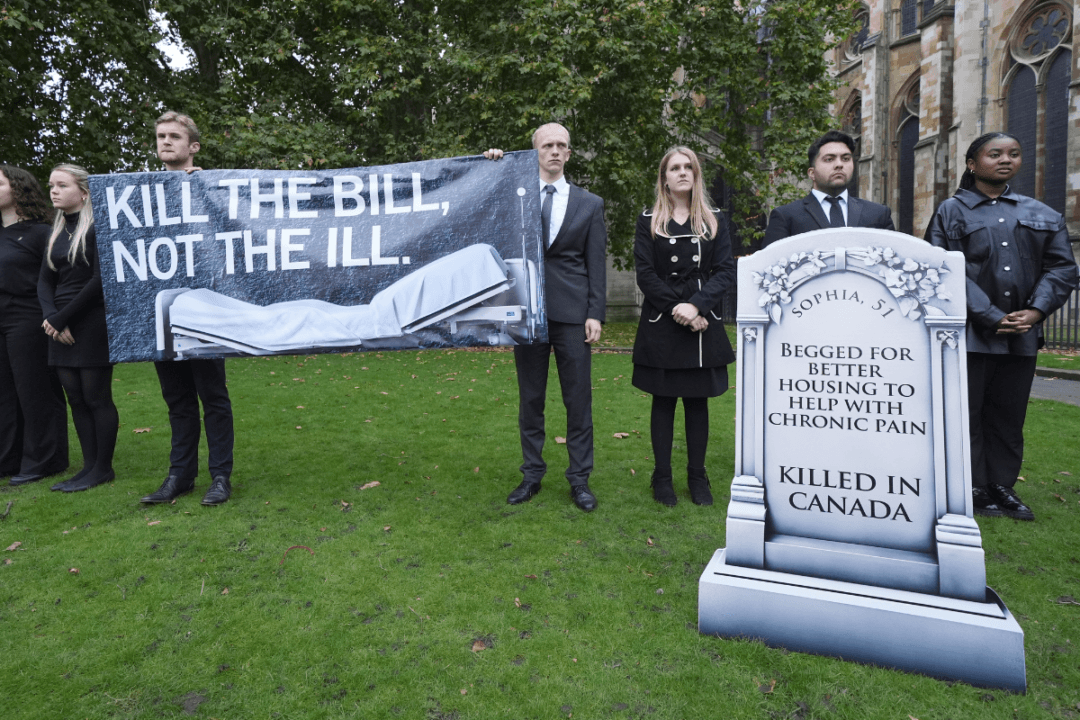

Canada’s assisted death policies have been in the spotlight in the UK as MPs there have been mulling legalizing euthanasia in recent weeks. Some raised concerns about a “slippery slope” effect that could result in the law becoming less stringent over time.

Canada’s experience was cited as an example of laws becoming increasingly more permissive following the legalization of euthanasia.