As Canadians from Newfoundland to British Columbia prepare to celebrate the nation’s 152nd birthday on July 1, the phrase “from coast to coast” brings to mind an epic chapter in the history of the country.

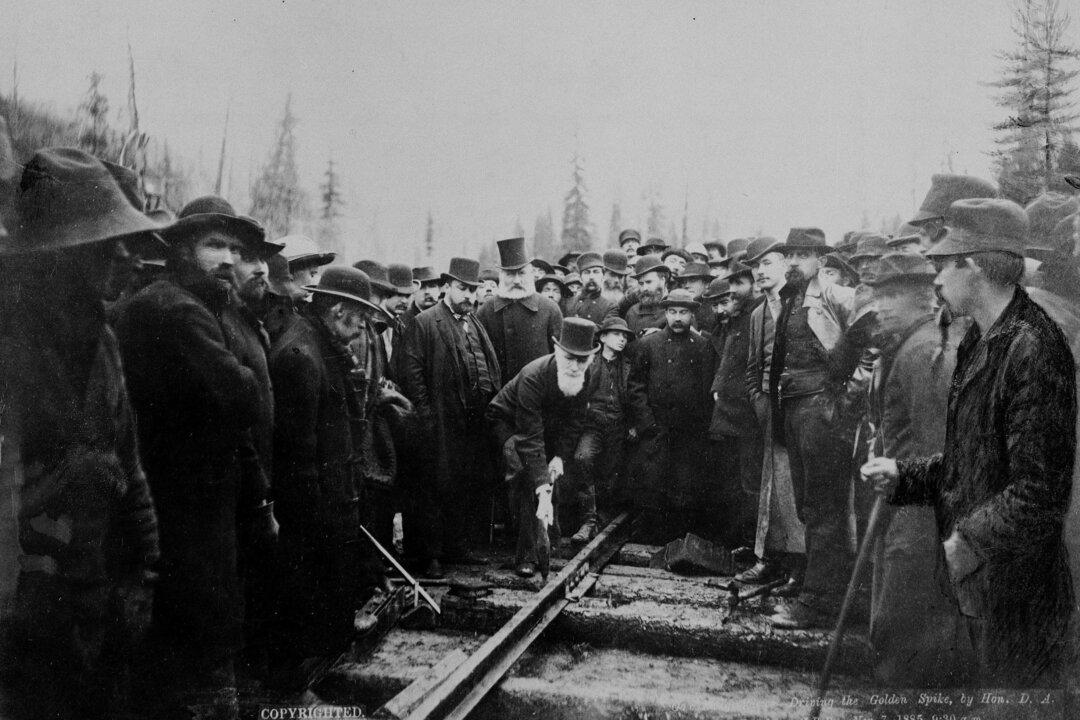

It is the story of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), which melded the country together from coast to coast, and of the towering figure of William Cornelius Van Horne, who simultaneously pulled off the spectacular feat of railway construction and nation building.