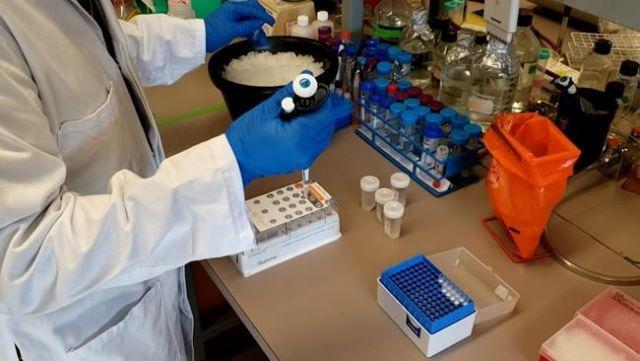

VANCOUVER—A national agency leading a network of labs hunting for variants of COVID-19 is aiming to double its efforts across Canada as part of a global surveillance initiative to keep up with new strains that may become more prevalent.

Viruses naturally mutate over time, and several COVID -19 variants of concern have been identified, including those that were first associated with the United Kingdom, South Africa, Brazil, and Nigeria, all of which have been detected in Canada.