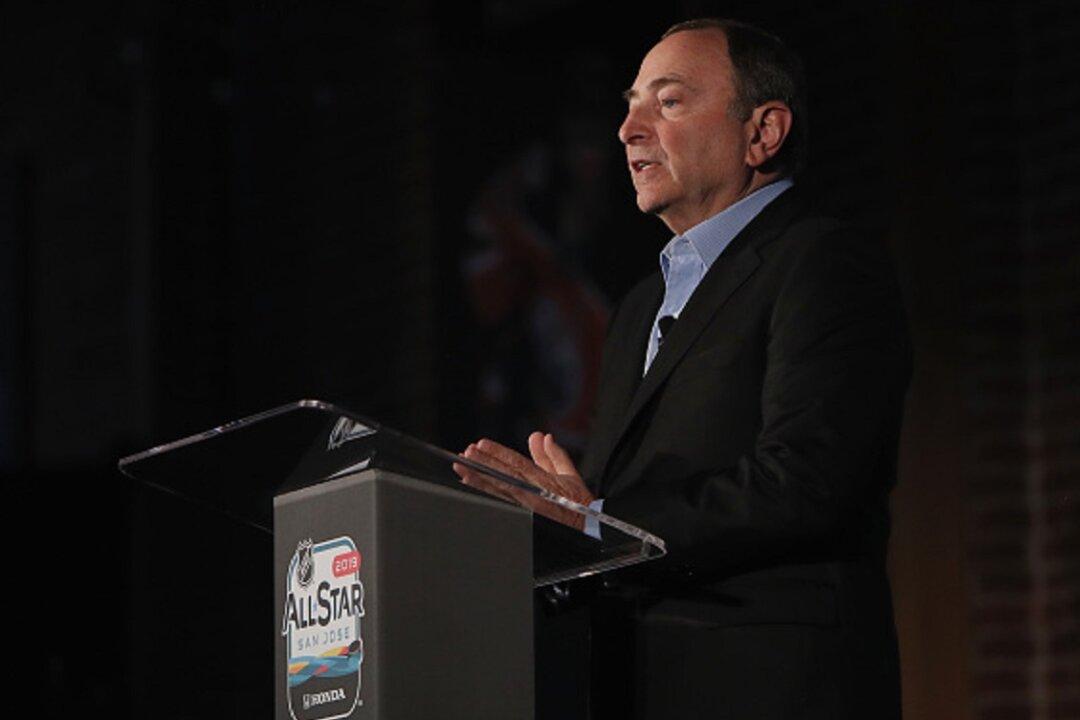

OTTAWA—The commissioner of the National Hockey League hit back Wednesday, May 1, at the notion of banning any kind of head contact in hockey, telling a parliamentary panel that such a rule would be impossible to enforce and lead to the end of hitting in hockey.

The league has faced calls to penalize any head contact in the hope of eliminating potentially debilitating concussions. Those calling for a strict rule include Ken Dryden, the former Montreal Canadiens goalie and cabinet minister in Paul Martin’s Liberal government.