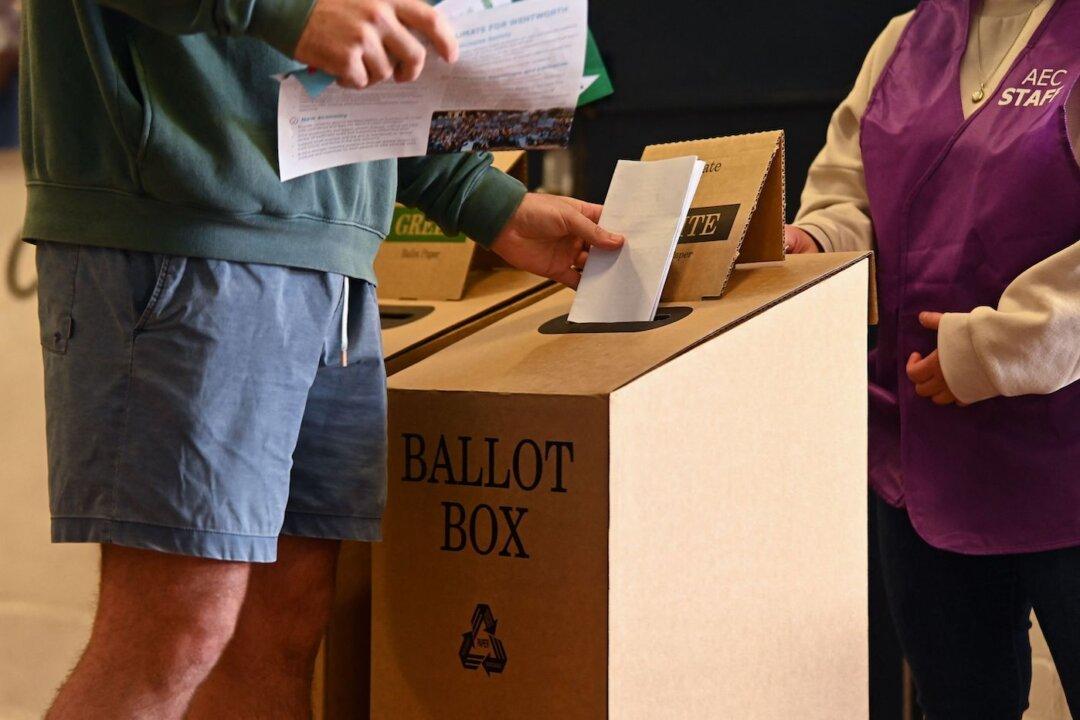

Australian voters cast ballots on Saturday to decide the next prime minister, as well as senators and members of Parliament, after a six-week election campaign that often centred on the economy and national security.

Electoral Commissioner Tom Rogers said Friday that 7,000 polling stations have opened as planned, despite a 15 percent turnover of its 105,000 workforces across Australia in the past week.