The Australian city of Sydney has installed over 100 nest boxes to serve as homes in place of the wildlife sanctuaries destroyed amid land clearing, urbanisation, and other human impacts.

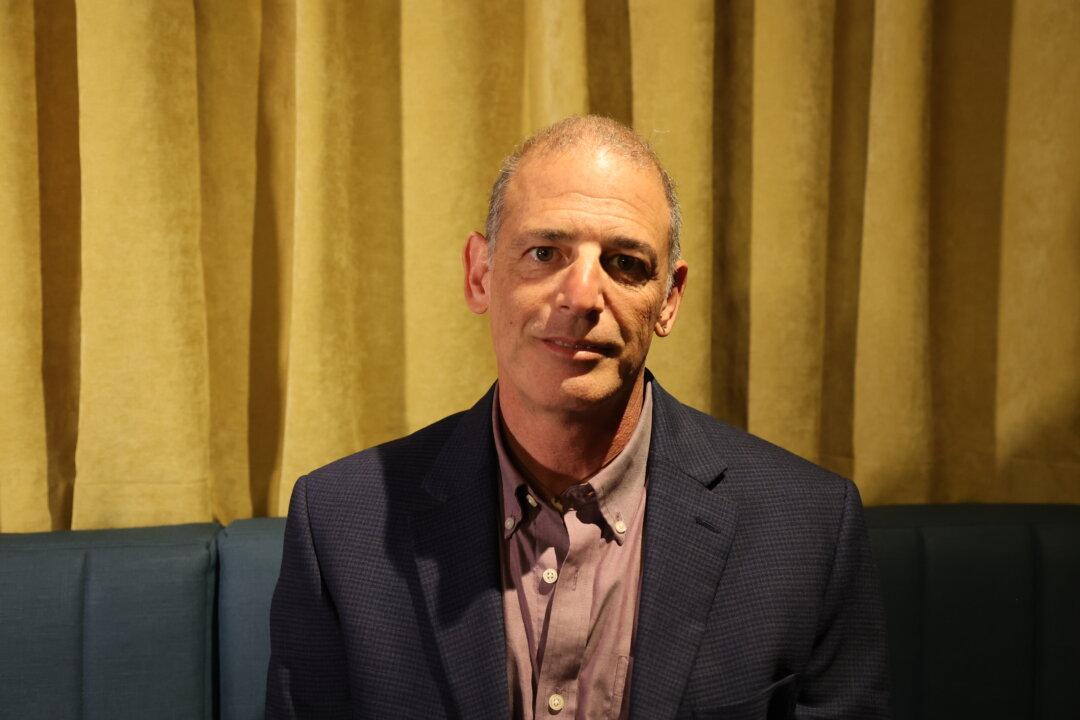

Nest boxes—designed for animals to roost, nest, rear their young, and use as a temporary shelter from poor weather—provide much-needed accommodation for Sydney’s other “housing crisis,” urban ecologist James Macnamara said.