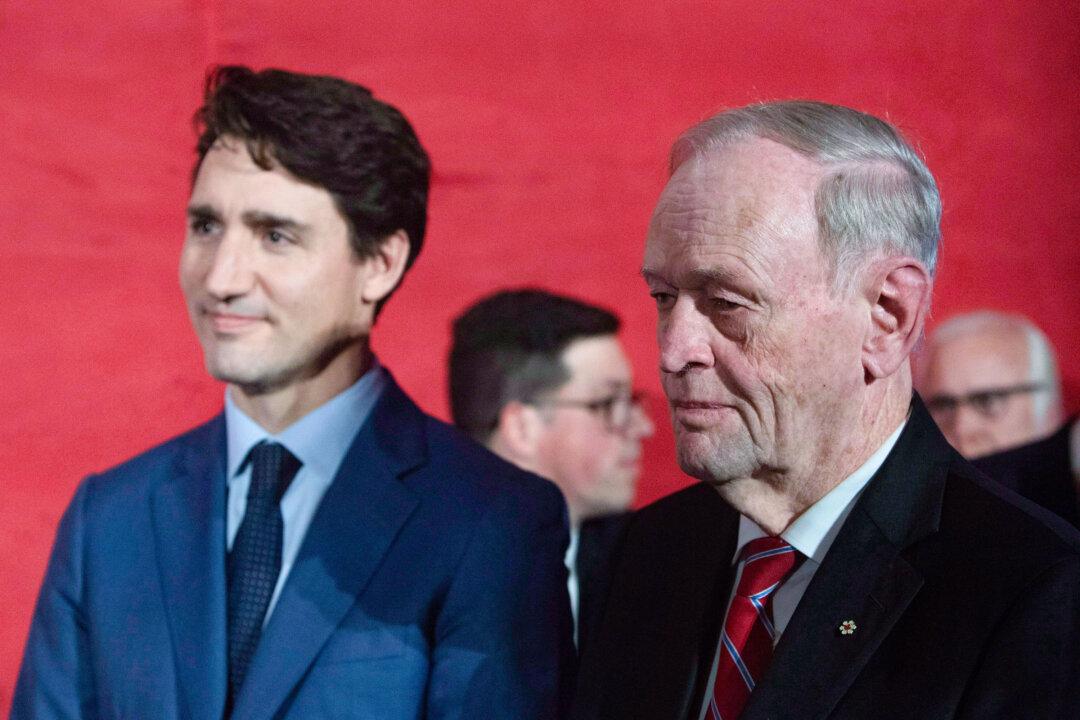

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau so far appears to have weathered the storm after the surprising June byelection upset in the longtime Liberal riding of Toronto–St. Paul’s. He has said he is committed to staying on as prime minister, and there are a number of factors working in his favour.

Back in the early 2000s, Paul Martin managed to displace Jean Chrétien as prime minister at a time when the Liberal Party had a comfortable majority in the House of Commons and had up to that point faced a fractured opposition.