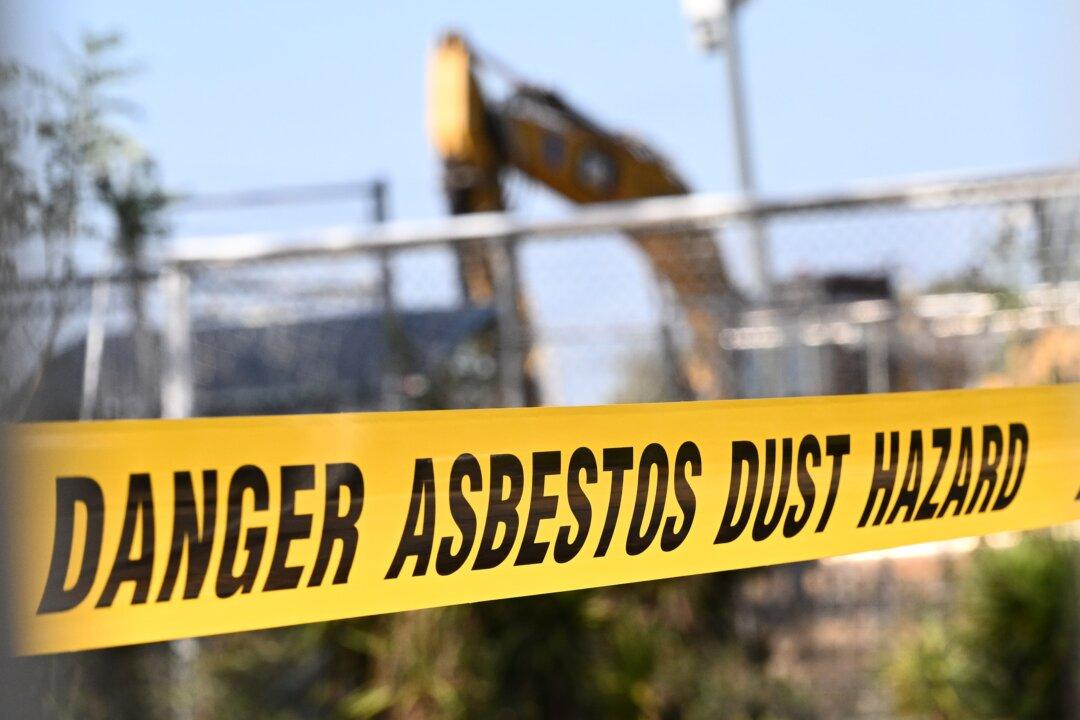

The tiny, isolated town of Wittenoom in Western Australia has come before the U.N. Human Rights Council, as Aboriginal traditional owners step up their fight to have the state government clear asbestos contamination from the site.

At the foot of a deep gorge 15 hours’ drive northeast of Perth, the Pilbara town is blanketed in the deadliest type of asbestos, crocidolite.