A gene therapy that usually costs £2.6 million per infusion has been approved for use on the NHS to treat a type of haemophilia.

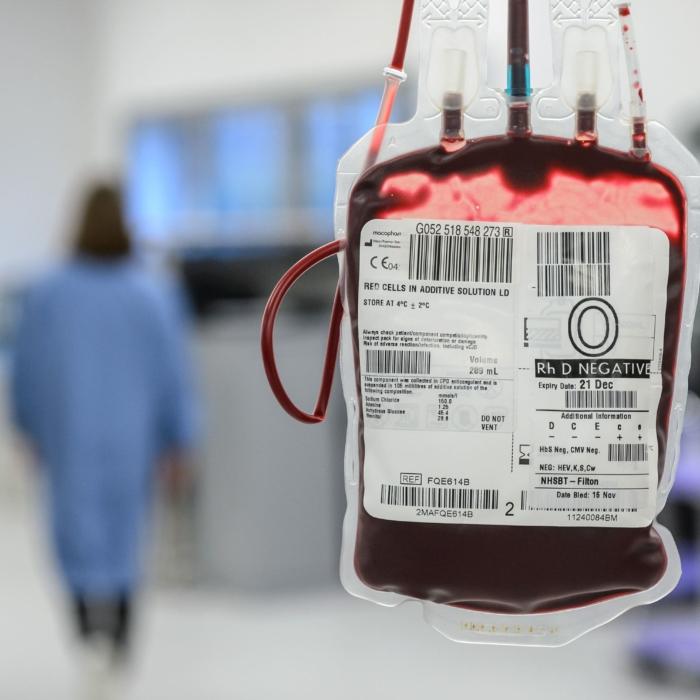

Sold under the brand name Hemgenix, the drug has been hailed as potentially “life-changing” for patients who will no longer require once or twice weekly blood infusions to put a missing protein essential for clotting into their blood.

The actual cost to the NHS is unknown as health officials have negotiated a confidential deal with manufacturers GSL Behring, meaning the sum paid could be considerably less, with the final amount dependent on how successful the drug proves over the next decade. It is believed to be the first time that the NHS has negotiated a “performance related” price for a drug.

If the gene therapy is successful, it should eliminate the need for regular treatment for at least three years and potentially beyond a decade. Regular clotting factor injections cost between £150,000 and £200,000 per patient per year, for life.

Approval of Hemgenix follows the completion of phase 3 trials and could benefit around 250 men in the UK who live with the condition. While around 2,000 males in the UK have type B haemophilia, the new therapy will only be made available to adults whose factor IX protein levels are less than 2 percent of normal.

‘Pioneering’ Drug

Professor Sir Stephen Powis, NHS national medical director, said in a statement, “It is a one-time therapy that could be truly life-changing for some, as it could help people avoid the need for regular hospital visits.”“This promising drug is the latest in a series of pioneering gene therapies secured for NHS patients at an affordable price and becomes the first drug to be made available in our Innovative Medicines Fund to provide early access for patients while further data is collected on its long-term benefits.”

Haemophilia is a hereditary genetic disorder, almost exclusively affecting men, that impairs the body’s ability to make blood clots. This results in people bleeding for longer than usual after an injury, easily bruising, and an increased risk of bleeding inside joints or the brain.

There are two forms of haemophilia: type A, a deficiency of blood-clotting protein factor VIII, and the rarer haemophilia B, a deficiency of factor IX protein.

Clive Smith, chairman of the Haemophilia Society, said in a statement: “The availability of gene therapy through the NHS for people living with severe haemophilia B marks a major milestone for our community.

“At its most effective, gene therapy has the potential to transform lives by eliminating painful bleeds and removing the need for regular, invasive, treatment.

‘Viral Vector’ Technology

The gene used for the therapy is placed inside a viral vector, which is described as an inactivated virus, meaning it should not spread in the body.Once the gene therapy is delivered through an infusion, the liver should start making its own factor IX, without the gene becoming part of the recipient’s DNA.

The therapy may not work for every recipient, however, and is not reversible.

The Haemophilia Society warned of potential side effects, including that: “It is theoretically possible that gene therapy could get into your DNA. If this happened, the person might be at increased risk of cancer.”

“Fragments of the virus vectors used to get the gene therapy to the liver might be in the blood, semen and bodily waste. This means a person who has had gene therapy can’t donate blood or semen or be an organ donor. There is also a chance that these fragments could be transmitted during sex which means condoms or other barrier contraception should be used for up to a year after the gene therapy infusion.”

More than 4,600 haemophiliacs were infected with hepatitis C and HIV after receiving contaminated blood products supplied by the NHS over several decades in what became known as the infected blood scandal.

A six-year inquiry concluded earlier this year with the publication of a 2,000-page report labelling the scandal, in which infected blood products were imported from the United States, “the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS.”

Despite allegations of criminal wrongdoing and cover-ups, no government, health care, or pharmaceutical agency has formally admitted any liability in the scandal, and compensation payouts are still being negotiated.