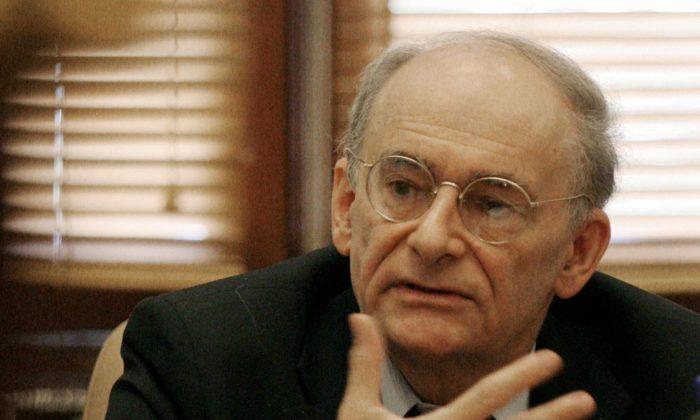

Allies in free countries can be a powerful force to help unshackle those suffering under brutal regimes, said renowned Canadian human rights lawyer David Matas, as he outlined how he and others worked with a Chinese lawyer to expose some of the Chinese regime’s most horrific crimes.

A Winnipeg-based international human rights lawyer and Nobel Peace Prize nominee, Matas spoke at a virtual panel exploring the modern context of Gandhi and human rights, marking the 150th birthday anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi on Oct. 4.

“We do not have to be inside a repressive country to resist the repression of that country,” Matas told the panel.

“Non-violent resistance has to shift from inside to outside. Commanding attention, spreading awareness, appealing to global opinion, bringing a mass movement into being cannot be done from within the country of repression. ... The Gandhis of today inside the country of repression, even just by demonstrating how little can be done from inside, can spur action from outside.”

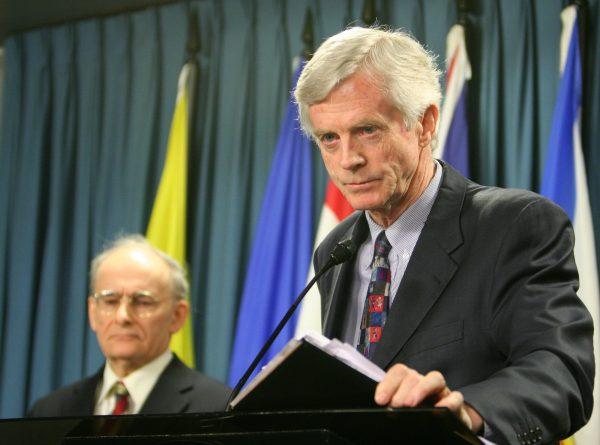

In 2006, Matas was pursuing an independent investigation into disturbing claims of the forced organ harvesting of Falun Gong prisoners of conscience in China. Working in concert with David Kilgour, former cabinet minister and Secretary of State for Asia-Pacific, the pair hit a roadblock: they wanted to go to China to do the work but needed an invitation from a representative within China to proceed. Chinese officials had already made it clear they only wanted to deny the evidence of organ transplant abuse in China, so Matas and Kilgour needed to find another way.

The person who eventually responded to their call, at great personal risk, was Gao Zhisheng, a renowned lawyer often referred to as the “Conscience of China” and who Matas likened to China’s modern-day Gandhi.

Gao, a self-taught human rights lawyer, was known for representing Chinese citizens who experienced persecution, including practitioners of the spiritual group Falun Gong. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) had launched a brutal persecution campaign against the peaceful spiritual discipline in 1999, in efforts to “eradicate” Falun Gong, as former CCP leader Jiang Zemin feared the increasingly popular practice was overshadowing his legacy. The CCP’s own data indicated there were more Falun Gong practitioners in China than Party members.

“The fact that Falun Gong were peaceful, unorganized, and apolitical did not stop Party power-climbers who were looking for an easy target,” Matas told the panel.

Practitioners were swept up in the large-scale persecution campaign; those who refused to give up their beliefs were imprisoned and tortured in labor camps across China. A few years later, rumors began to emerge that organs of these prisoners of conscience were being harvested without their consent to feed a lucrative organ trade, while their bodies were cremated to hide the evidence.

Starting in late 2004, Gao repeatedly sent letters to senior CCP officials, demanding changes to the suppression of Falun Gong adherents and other oppressed groups. The CCP responded with escalating harassment and threats against him.

By the time Gao invited Matas and Kilgour to investigate in 2006, the CCP had revoked his license to practice law, put him and his family under police surveillance, arbitrarily arrested him and his office staff, and were suspected of attempted assassination after a military vehicle tried to run Gao down in the street.

Yet in his reply to Matas, Gao assured him that the risks of inviting the Canadians to investigate the forced organ harvesting of Falun Gong practitioners were far outweighed by the ever-present danger of living under “an evil dictatorship system.”

Matas-Kilgour Report: ‘Bloody Harvest’

What Matas and Kilgour eventually found in their investigation, detailed in their 2006 report “Bloody Harvest,” was evidence of state-sponsored illicit organ harvesting. Falun Gong prisoners of conscience were being used as a living organ bank to supply China’s lucrative organ transplant trade, they concluded.Among the evidence considered for the report were phone calls made to Chinese transplant doctors, in which the doctors admitted to harvesting organs from Falun Gong practitioners.

Gao’s Courage

Gao’s courage and willingness to work with Matas was instrumental in uncovering this atrocity, and shows how powerful these types of collaborations from inside and outside a repressed country can be, Matas said.“Gao Zhisheng did not prompt me to begin my work on the Falun Gong file, since I began the work before I knew of him, but he surely encouraged me to continue and persevere,” he said.

“If he was prepared to risk so much for so long, I, from the safety of Winnipeg, should do what I could.”

Gao was released from a three-year prison sentence in China in 2014, but was rearrested in August 2017 and his whereabouts remain unknown.

Gao displayed exceptional heroism and put himself at great risk to help others, said Matas, but noted that there are countless other ways to help support victims of persecution in China like Falun Gong adherents, without danger. His speech to the panel included 18 recommendations for measures that could be taken in the fields of medicine, law, business, and research that would have a profound effect toward stopping the persecution and illegal organ harvesting.

For example, Matas said Canada should require provinces to report all cases of transplant tourism and re-enact an existing bill that would make complicity in transplant abuse abroad an extraterritorial offense, while imposing an immigration ban on those complicit in organ transplant abuse.

He said Canada should also apply Magnitsky sanctions to Chinese officials directly involved in the persecution of Falun Gong—a request made to the Liberal government by the Falun Dafa Association of Canada in 2018.