Commentary

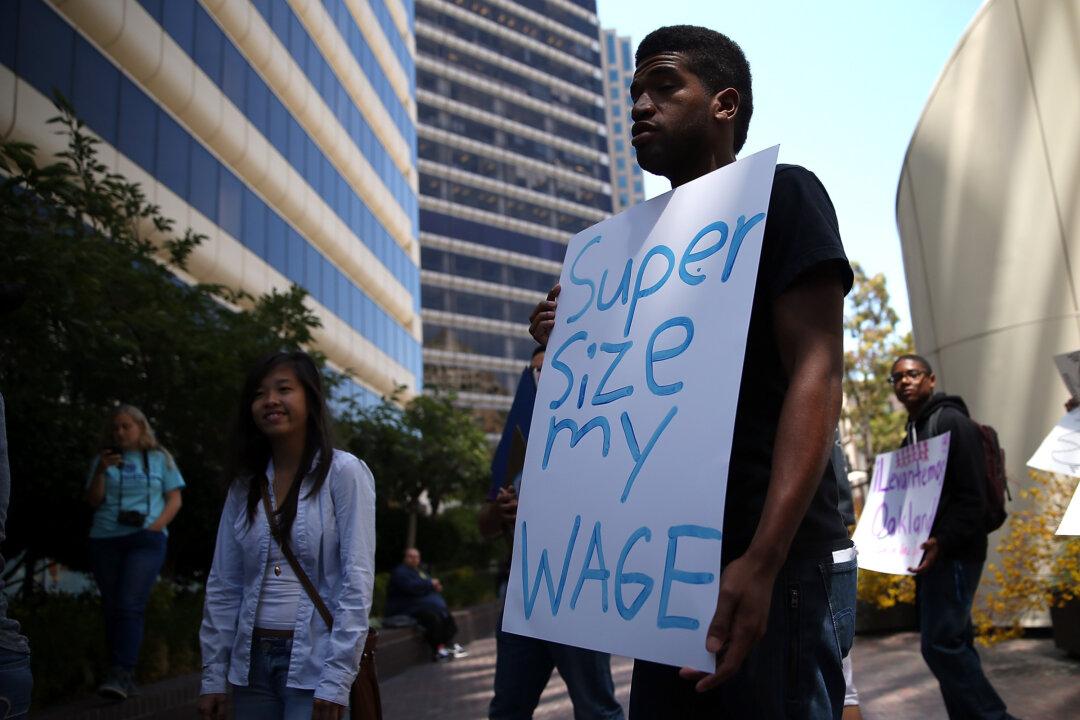

Here we go again. The latest scheduled round of minimum-wage increases, to $15 per hour ($14 for small companies), starts Jan. 1. It hasn’t even gone into effect, yet calls are going out for a $18 wage. Why not $28? Or $58? Or $118?

Here we go again. The latest scheduled round of minimum-wage increases, to $15 per hour ($14 for small companies), starts Jan. 1. It hasn’t even gone into effect, yet calls are going out for a $18 wage. Why not $28? Or $58? Or $118?