Commentary

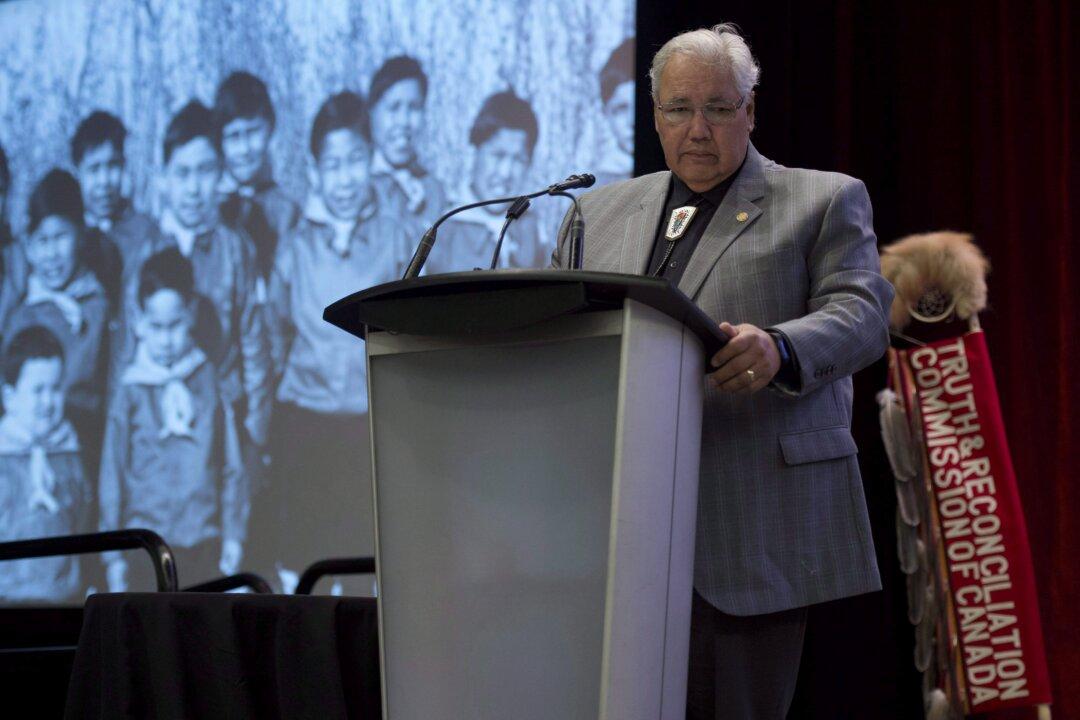

The first couple of sentences in the final Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) report contain a stark condemnation of the way Canada has treated its indigenous peoples:

The first couple of sentences in the final Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) report contain a stark condemnation of the way Canada has treated its indigenous peoples: