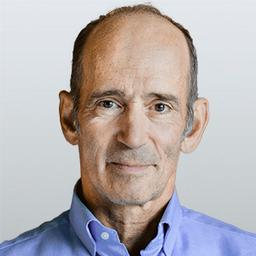

In this interview, Dr. Paul Saladino, author of “The Carnivore Code”—a book on nose-to-tail animal-based eating—reviews what it means to be healthy at the most foundational level and shares his findings from a recent trip to Africa where he visited the Hadza tribe, who are among the best still-living representations of the way humans have lived for tens of thousands of years.

Like the !Kung tribe in Botswana, the Hadza live a hunter-gatherer life amidst the encroachment of modernized society.