Commentary

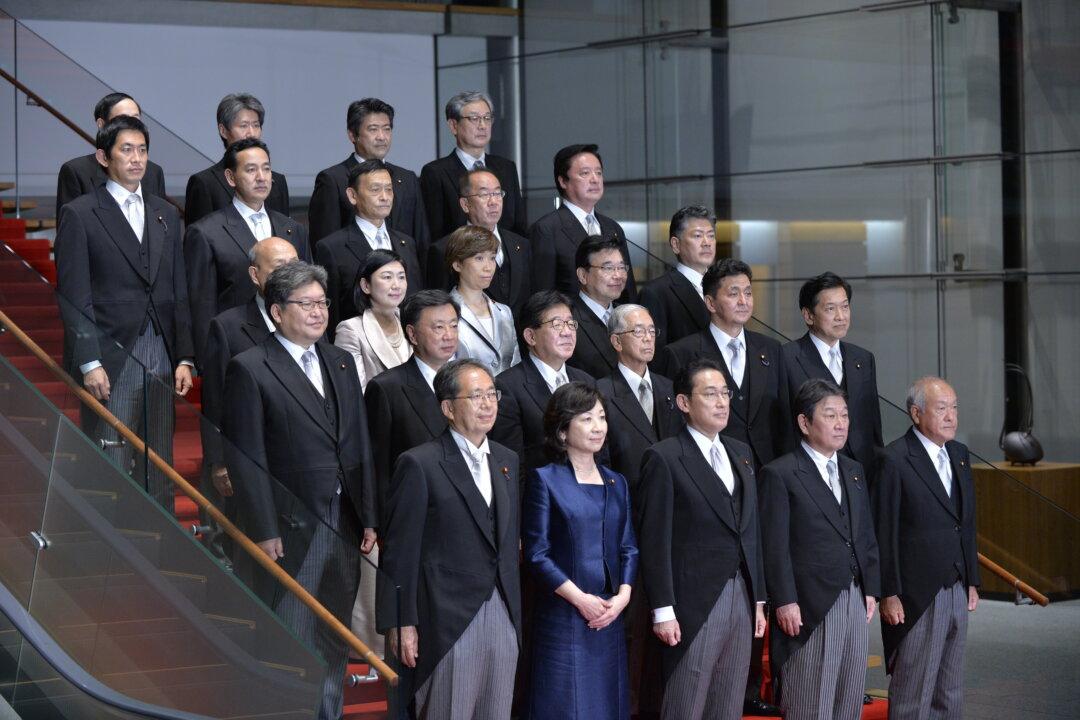

Fumio Kishida was recently elected as the 100th prime minister of Japan after winning the Liberal Democratic Party’s (LDP) leadership election and succeeding Yoshihide Suga. With the change in Tokyo’s leadership in short succession from Abe to Suga and now Kishida, Japan’s neighbors—especially China—are assessing the situation. Beijing is concerned that Kishida is a hardliner in promoting and securing Japan’s interests.