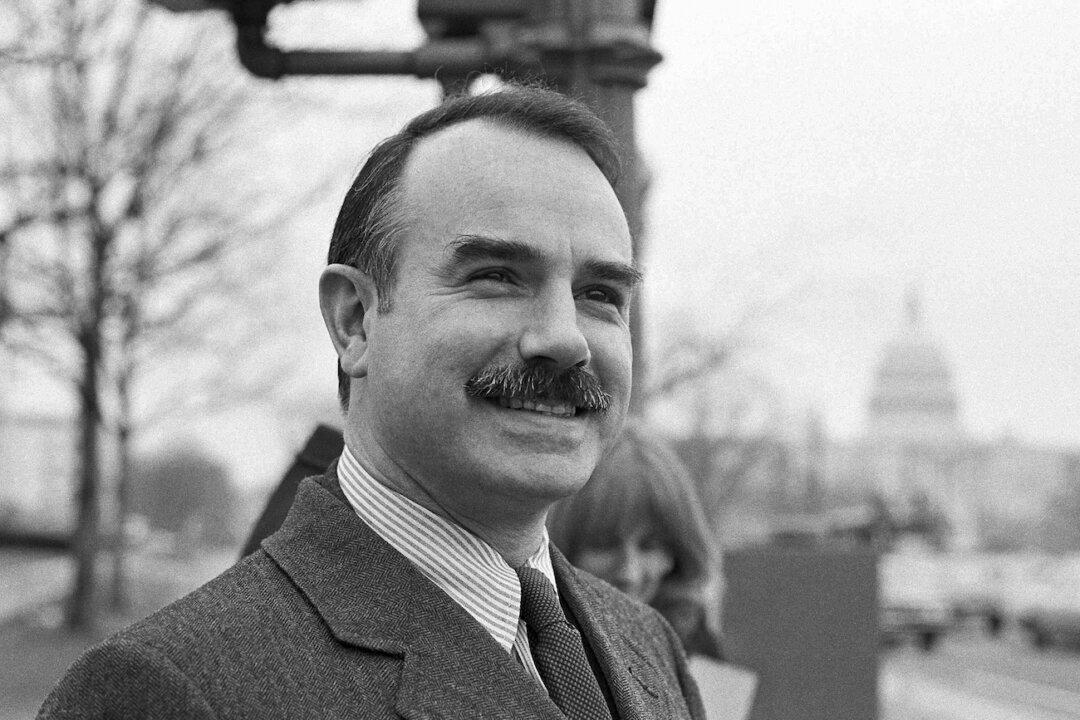

G. Gordon Liddy, a former FBI agent who helped orchestrate the 1972 Watergate break-in, a crime that began the unraveling of Richard Nixon’s presidency, died on Tuesday at the age of 90.

Liddy, who leveraged his Watergate fame into a 20-year career as a conservative talk-radio host, died surrounded by family at the home of his daughter in Mount Vernon, Virginia, his son, Thomas P. Liddy, told Reuters by telephone.